When ‘10,000 Voices Rang Out As One’ in Minnesota

Once upon a time, Minnesotans gathered in local parks for "community sings" competitions.

‘Minneapolis is Teaching America to Sing’

That was the banner headline of the Minneapolis Tribune 90 years ago. The flour milling capitol of the world, the Mill City was also a leader in another offering that caught the country's attention: a uniquely Minnesotan approach to community singing.

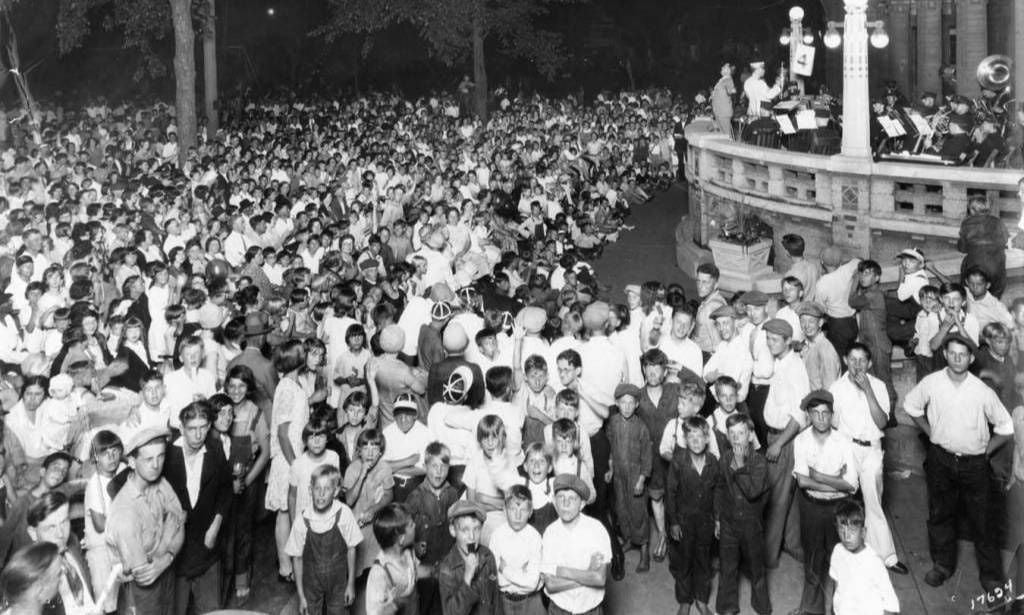

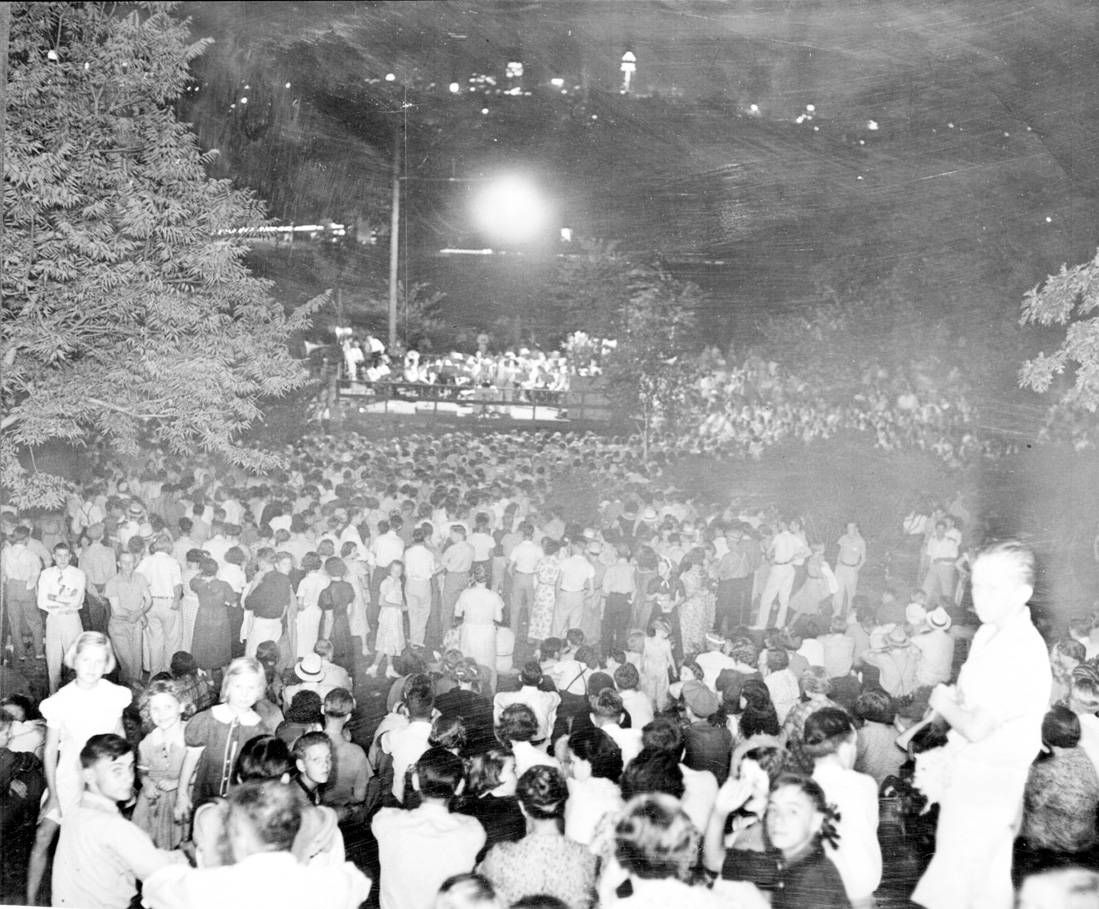

Known as "community sings," the events were public mass-choir competitions held in Minneapolis parks during the years between the world wars. During these decades, tens of thousands of voices would rise up out of city green spaces and fill the air on summer evenings, epitomizing the "village green" ethos of parkland founders described in the Twin Cities PBS documentary Parks for the People.

The community sings movement began in 1918 as a series of patriotic offerings in parks across the country during World War I. The Minneapolis Tribune began co-sponsoring the events in 1922, and the singalongs gradually grew in attendance and popularity over the next decade, in no small part due to the paper's extensive - and rather self-congratulatory - reporting on the competitions.

During the Great Depression, the crowds swelled during those muggy, summer gatherings, and the competition between parks and neighborhoods heated up, too. Songs featured during the concerts always included patriotic selections, but conductors leaned in to beloved, popular and syrupy-saccharine tunes like "I'm Forever Blowing Bubbles," "Kiss Me Again" and "K-K-K-Katy."

Participatory, public entertainment clearly held enough power and potency to draw thousands of people from their homes with the singular motivation of singing in unison. In addition to the innate, human connection to song, the events played to our tribal nature. Ratcheting up the competitive fever, the sponsors playfully pitted parks and their surrounding neighborhoods against each other. Parks were rated in categories such as "enthusiasm," "attendance" and "crowd conduct," and the paper would report on one park's performance as a challenge to the next park. If Folwell scored well on "crowd conduct" or, say, Camden or Logan Park notched high points for "deportment," then Powderhorn might be able to top their total score with a high attendance, an advantage of the southside park that is essentially a 470-acre natural amphitheater around a lake.

One newspaper account painted a vivid picture of proto-flash mobs from nearly a century ago:

'Through the park entrance they drift, moving forward towards a lighted bandstand. They seat themselves on park benches. They find a quiet, secluded spot under friendly trees. They loll about on green grass. Here and there a cigar glows. A fan flutters. But suddenly, the band strikes up…the first chord of the band drifts into a rollicking tune. They sing. Slowly and perhaps a little diffidently at first, the crowd picks up the refrain. Then, gathering power and momentum as the volume grows, 10,000 voices ring out as one, and leap into the blackness of the night.'

Try and have that experience in a Zoom chat.

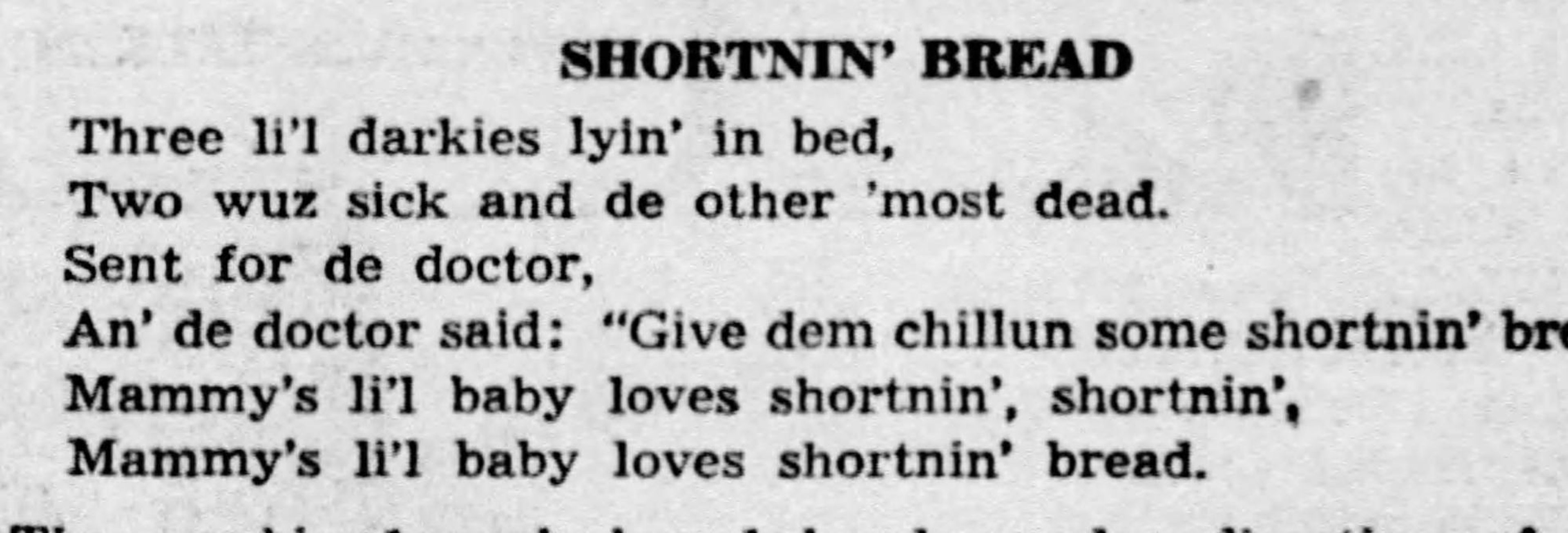

The lyrics were provided by the newspaper for the community sings gatherings. Unfortunately, it won't come as a surprise that, during a time when a system and culture of "Jim Crow of the North" was settling in on the city, there were awkward and culturally offensive facets of these community events.

Indeed, many of the songs sung in Minneapolis parks on those balmy summer evenings would make us shudder today. Case in point: the song "Shortnin' Bread" with its use of the slur "darkies." Imagine 10,000 people belting those lyrics out en masse into the warm night. "Old Black Joe", the very popular ditty about an African American thought to be pining for the plantation, was another popular tune that unfortunately would have wafted out of the parks on summer evenings.

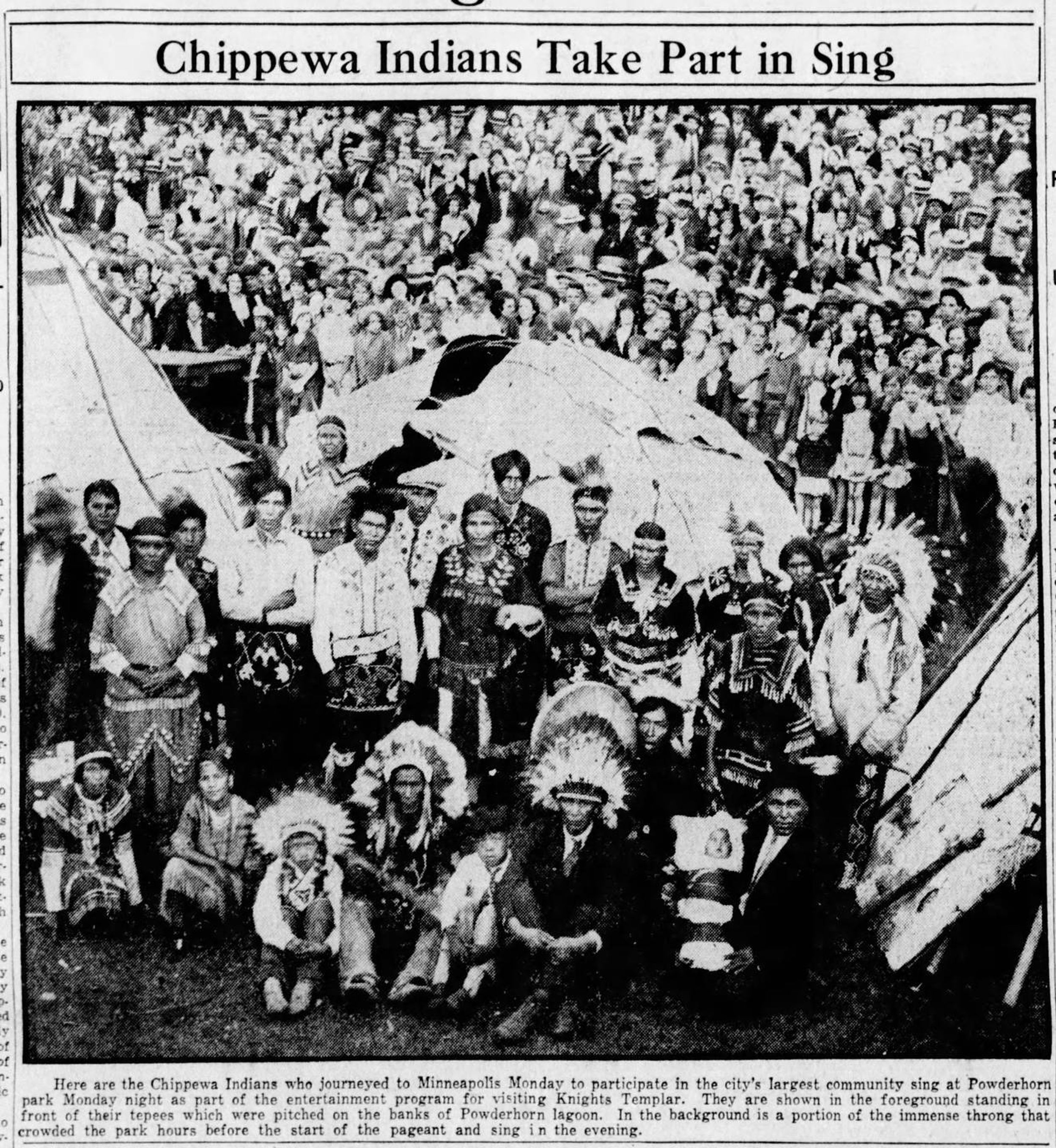

In 1931, members of the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe joined the sing at Powderhorn Park. The crowd seemed genuinely excited to have the band members, who were described in the colonized language of the time as "painted and be-feathered" and "camped out" near Powderhorn Lake, according to the report. But the Ojibwe drummers and singers added a quality to that evening's sing at Powderhorn Park, an event that was said to have drawn between 70,000 to 100,000 people, larger than many towns in Minnesota. At the time, reports described that event as the one that generated the most volume ever heard in the parks, a veritable "burst of song…a murmurous musical thunder."

The rest of the country began to take note. Other cities across the state and the nation pledged to replicate Minneapolis' mythical musical events. President Harding sent a congratulatory note to the city, lauding the events "good neighbor effect." Tourists from around the world urged other travelers visiting the City of Lakes to make sure to take in this singular event in the well-regarded parks of the city.

Just as we're having to reconsider how we gather in the parks due to the coronavirus pandemic, contagious disease proved to be the one force that could stop the community sings events…sort of. During the polio outbreak of 1946, when the feared disease grimly stalked children, the park board and the Tribune decided to cancel the live singings events. With the need for social distancing, they used the tech of the time to offer a "song in the air," with sing-a-long programming on local radio stations specifically aimed at kids who were sick in bed or just self-isolating at home.

By the mid '50s, the sings were folded into other music programming that might seem more familiar to people today who attend a musical event at a park. A community sing one night, an orchestra performance the next week. The numbers of people who congregated for singing in parks came down, too. One can't help but wonder if screen time - TV screens, in this case - were beginning to draw families away from the park bandstands and into their living rooms. In the mid '60s, Saint Paul Parks tried to pick up the community sings baton with smaller events in Phalen, Como and Cherokee Parks. But the crowds from years past never showed up.

Powderhorn Park, the champion of the community sing era, began to see other gatherings fade away as well. The longstanding southside picnic, the speed skating competitions and, more recently, the iconic 4 of July fireworks all went up in smoke. And in 2019, the May Day parade ended its traditional spring gathering at the park (which concluded with a mass sing along of "You Are My Sunshine") with hopes of returning in a new form in the future.

In recent years, groups like MNSing have invoked the storied legacy of community sings for music-based gatherings. Perhaps in the near future, after so much time apart, the "singing city" might be ready to gather en masse again and join in this singular experience that was unique to the power of place found in Twin Cities parks.

Visuals courtesy of the Star Tribune and the Minneapolis Parks & Recreation Board.

This story is made possible by the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund and the citizens of Minnesota.

Art cars – whether created by professional artists or amateur enthusiasts – delight crowds on any day. But when they show up unexpectedly in an impromptu neighborhood parade during a pandemic? Pure magic.

Just as the community sings events were unfolding in Minneapolis parks, notorious gangsters flocked to the "saintly city" on the other side of the river. Explore this slice of local history in which the criminal underworld hobnobbed with high society.

The iconic club known as First Avenue has long been a sort of ground zero for musical lovers of different stripes to gather. Take a trip in a time machine to visit the early days of the venue - first, when it was known as The Depot and later as Uncle Sam's.