Minnesota Central Kitchen Is on a Mission to Feed Hungry Minnesotans

GLOBAL CRISIS, LOCAL SOLUTION

For Liz Mullen, the world almost stopped turning on March 16, 2020. Minnesota Governor Tim Walz had signed Executive Order 20-04, ordering the temporary closure of bars and restaurants in response to COVID-19. Over the next year, restaurants would struggle to adapt to changing guidance and limited operation, some closing forever.

As restaurants worked to serve customers under new orders and mandates, many restaurant employees worked limited hours or were laid off entirely. Thousands of Minnesota workers in other sectors also lost work and wages, resulting in the largest surge in unemployment applications ever and a growing number of families experiencing food insecurity.

At the same time, the creative and pragmatic minds at Second Harvest Heartland were cooking up ways to solve a global crisis with local solutions. That’s how Minnesota Central Kitchen was born.

“Minnesota Central Kitchen is a collaboration of chefs, restaurateurs, food service professionals, food recovery, furloughed hospitality industry workers and a need to make meals in response to COVID-19,” says Emily Paul, director of the Minnesota Central Kitchen project, which is a program of Second Harvest Heartland.

Chowgirls Catering approached Second Harvest Heartland with the idea after all of their large-scale catering events – like weddings and conferences – were cancelled almost immediately. With an abundance of fresh foods that would soon go to waste and a workforce hoping to stay employed, Executive Chef Liz Mullen got to work and started networking.

“Watching our team jump into action was amazing,” says Mullen. “There’s no other team I would want to go through an apocalypse with.”

Mullen remembers feeling energized by the solutions that came together quickly as the entire state of Minnesota navigated a new world.

NEW SOLUTIONS TO OLD PROBLEMS

“What can we do to help?” That’s the question Emily Paul remembers Mullen asking. “Two-and-a-half days later,” Paul says, “we produced about 2,500 meals.” And each of those meals was donated to help alleviate the surge in hunger that thousands of Minnesota families experienced as COVID-19 first came to the state.

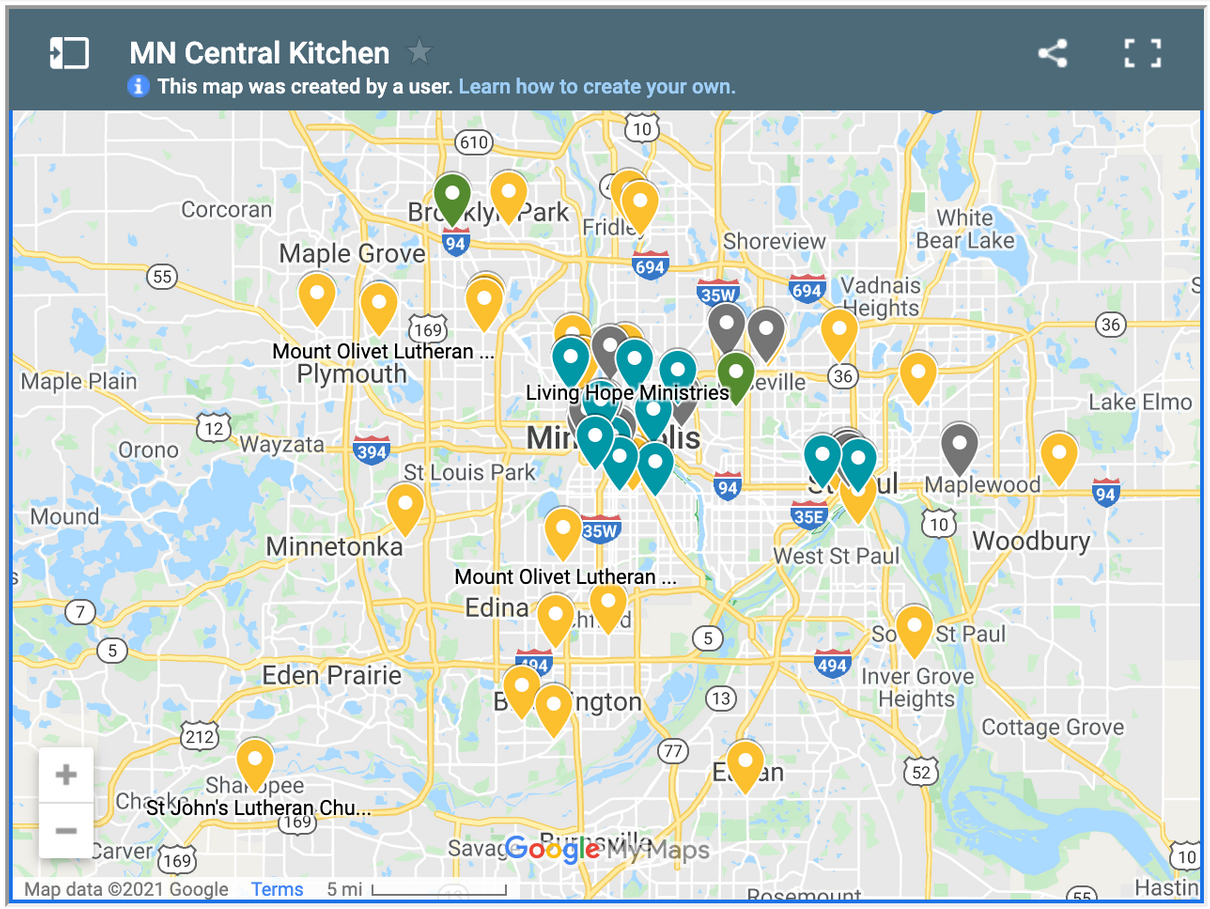

“That same week, we were talking with Chowgirls, Loaves and Fishes came to the table and said, ‘We can be your distribution, we can be your food safe facilities for getting these meals out to people,'” says Paul. “So that partnership then has grown into other like-minded community organizations that work with different diaspora populations, different cultural groups, different geographic areas to ensure that these Minnesota Central Kitchen meals make it out to all those in need, from families who are food insecure in Roseville, to folks who are living in homeless encampments in Minneapolis, to different cultural organizations throughout the Greater Twin cities who have food and cultural or ethnic preferences in their dietary preferences, we want to make sure that we’re acknowledging that and servicing those needs as much as possible.”

Over the next year, Minnesota Central Kitchen would prepare and deliver more than 1.3 million meals to hungry Minnesotans.

“From farmer to chef, to our hungry neighbors, Minnesota Central Kitchen has inspired me to search out answers to our food problems,” says Mullen, “and to be curious and connect with others to help solve our food waste issues and food insecurities.”

TRADING DISPARITY FOR OPPORTUNITY

As the pandemic unfolded, existing disparities across the socioeconomic spectrum were thrown into sharp relief. Communities of color experienced higher rates of infection and worse outcomes, as well as greater losses of wages as industries like food service and hospitality halted.

Recognizing the importance of equity was a guiding principle from the beginning of Minnesota Central Kitchen.

“So in terms of other disparities within the food system and food sector, creating employment opportunities with this program, we will have reemployed approximately 190 food service workers… Those are folks that would probably not otherwise have a job right now. They are making meals for people in our community.”

And by keeping workers employed, it’s likely the program has also played a role in preventing the need for additional unemployment and hunger-related services. Although Chowgirls Catering did have to lay off some staff, they were also able to reassign servers that would otherwise have been unemployed. Through the Minnesota Central Kitchen, Chowgirls has been able to keep, hire or rehire around 50 staff.

“So addressing some of those disparities and missed opportunities because of COVID, we want this program to be able to address some of those and to the best of our ability create opportunity instead of disparity with COVID-19.”

FOOD RESCUE AND ADDED BENEFITS

Paul estimates that between 60% and 70% of ingredients used in Minnesota Central Kitchen meals are rescued. A large portion of ingredients came from on-farm food recovery – which ensured that farmers received income that might otherwise have been lost to dissolving markets. Still other ingredients came from retailers and big-box stores with produce near expiration dates; and another portion came from food bank donations.

Rescued food takes many forms, but much of it comes from farms that have a surplus during harvest season, or from packaged foods that still hold integrity but may have labeling mistakes, for example.

“Rescuing food is one of the biggest sources of food that we access for hungry Minnesotans,” says Allison O’Toole, CEO of Second Harvest Heartland. “So it comes from a lot of different areas. We work with food shelves and meal programs to help coordinate the rescue – from retailers, from grocery stores, from convenience stores, from farmers – to make sure that we’re using every ounce of food that we can.”

O’Toole estimates that Second Harvest Heartland rescues about 40 million pounds of food every year, with over 1.4 million pounds of that going directly to Minnesota Central Kitchen meals.

Rescuing food also reduces the amount of waste ending up in landfills.

“Mitigating waste in the environment, I think that’s really important,” says Paul, “so thinking about on-the-farm rescue and what we’re able to do with it is pretty astonishing and pretty great.”

“It’s part of our responsibility to this environment to limit food waste, but it’s a win-win for us,” echoes O’Toole. “We can rescue that, we save it from the landfill, and that is a way to provide fresh, healthy meals to so many communities that need it.”

This story is part of the Twin Cities PBS original series At The Table, which examines social and systemic issues within our food environment. Funding provided by the Cargill Foundation.

Hunger takes many forms in Minnesota: Parents skip meals so their children can eat, they water down milk so there’s enough to go around or they make soup out of ketchup packets. But when it comes to how we talk about the lack of steady access to fresh, healthy foods, buzz words abound – food deserts, food swamps, food access. So what does the term "food insecurity" mean in Minnesota?

Wondering what kind of good work is unfolding to tackle food justice across the country? Check out the efforts led by these three change-makers who seek out ways to promote ancestral connection and spirituality through agricultural projects.

George Floyd’s police killing has brought together communities in a show of resilience – but it’s also revealed deep-seated racial inequities in access to healthy food now that the Lake Street area, where many grocery stores were damaged or destroyed, has become a food desert. Almanac reporter Kyeland Jackson examines how that lack of food access is actually rooted in racism-charged issues related to access to jobs and opportunities to build wealth.