Why did high-tech giant Honeywell trigger a decades-long public protest?

The United States' involvement in World War II had broad support from the American people. In the minds of nearly any American, it remains one of the most clearly justifiable wars in our history. Through the flames of Pearl Harbor, the enemies seethed with villainy. Men proudly enlisted, and women leaped into crucial, strenuous roles in the American industrial workforce. We fought. We labored. We overcame. We crushed tyrants and extinguished fascism. The massive wartime industry gave our postwar economy a huge head start. Job well done.

Fast-forward to America in 1968 - 23 years later, and things couldn’t have looked more different on the home front. And for at least one high-tech company that proudly participated in wartime industrial production in World War II, things were about to get…complicated.

Honeywell (through its predecessor companies) had been producing gadgets since the 19th Century, mastering a range of control systems after pioneering the electric thermostat. Like many companies, the opportunity to turn its expertise to wartime production had both patriotic and capitalistic rationale. Honeywell was given the contract to manufacture the Norden bombsight, an analog computer that was crucial for improving bombing accuracy for the Allies. In fact, Honeywell matched the autopilot system with the bombsight so that they functioned in concert.

That interest in military and avionics technology only grew after the end of the war, boosted by the continued development of jet aircraft and nuclear weapons technology. By the 1960s, Honeywell was nicely positioned in the military market, just in time for America’s entry into the Vietnam War. Honeywell developed cluster bombs, guidance systems for nuclear missiles and other devices of war. While Honeywell was also developing cutting-edge computing technology for commercial use, the company's military work began to draw the attention of local citizens horrified by the nightly television images coming back from the campaign in Vietnam.

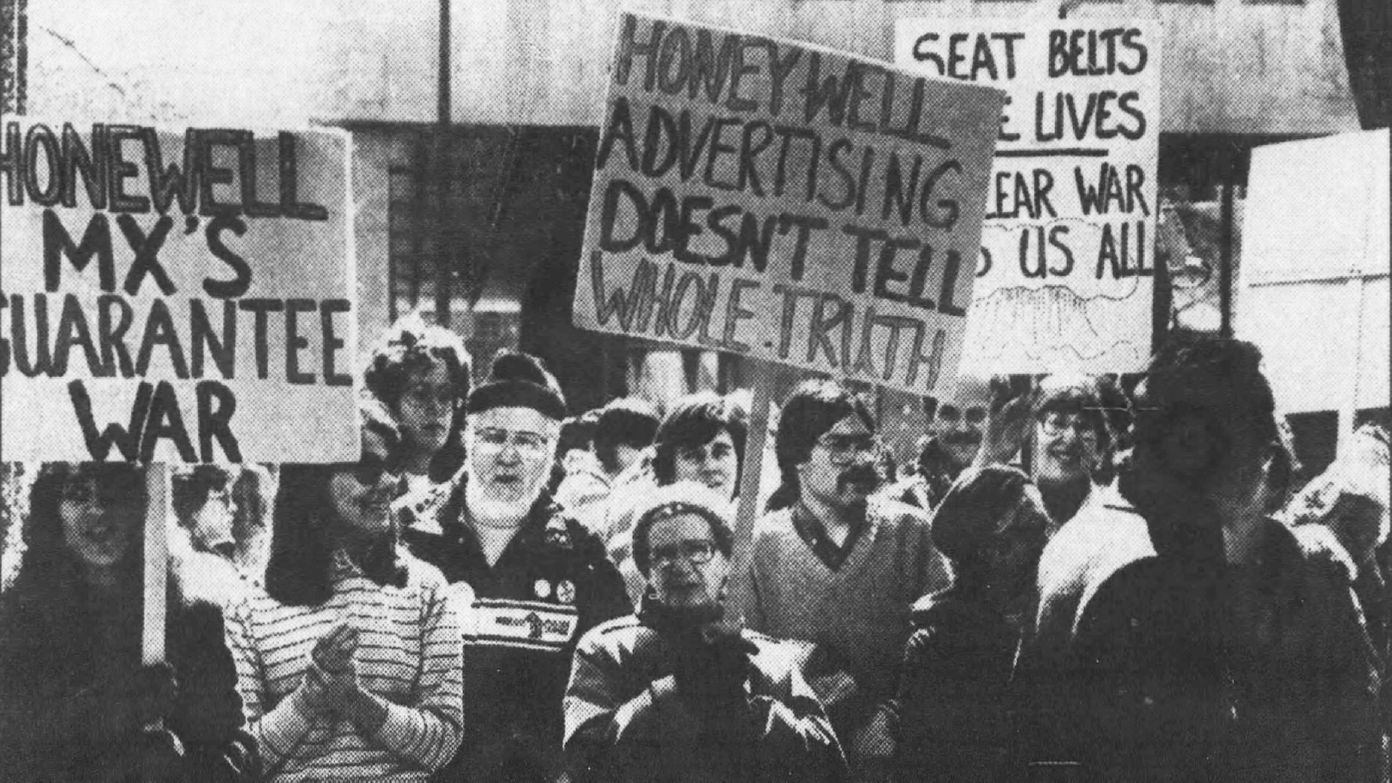

In 1968, a seasoned and passionate activist named Marv Davidov spearheaded what came to be known as the Honeywell Project, an extraordinarily long-running protest that continued until 1990. Unlike many protests of the era, the Honeywell Project was conspicuous in its civility and respect, aiming to make a public statement about the company’s business model without descending into violence and incivility. With the exception of a regrettable 1970 march, which did damage property and required police action, the Honeywell Project maintained peaceful protests for well over two decades.

As the movement grew, it attracted academic scientists from the University of Minnesota, leading society folks like Charlie Pillsbury and Mark Dayton, heirs to the food and retail dynasties, respectively. By the 1980s, nuclear proliferation and arms buildup under the Reagan administration widely escalated fears of nuclear war. Honeywell’s work on guidance systems for the Pershing II nuclear missile was no secret, and concerned Minnesotans of many stripes were drawn to the cause.

In 1983, a massive demonstration that led to the arrest of around 150 protesters put the issue on the front page for Minnesotans. The FBI amassed a file on Marv Davidov that numbered some 1,200 pages, and FBI agents infiltrated the movement.

The controversy only died down in 1990 when Honeywell reorganized its military work into a spinoff called Alliant Techsystems. The protest changed names at that point to AlliantAction, and continued local activities until the headquarters moved to Washington, D.C. in 2011.

In the end, the Honeywell project never really met its goal: to convince the tech firm to give up its military projects for more peaceful work. But it provided a direct outlet for concerned citizens in anxious times, from the quagmire of Vietnam to the mutually-assured destruction of the nuclear arms race. It gave concerned Minnesotans a way to engage with one of its most important and beloved industry-leading technology companies. And that makes The Honeywell Project an interesting and important part of Minnesota’s high-tech history.

Learn more about Honeywell's high-tech work in Solid State: Minnesota's High-Tech History.

It's true: Some of the world's most powerful - and secret - computing projects were developed right here in Minnesota. So how did the state become the land of 10,000 covert inventions?

Designed by famed architect Eero Saarinen in 1956, IBM's Rochester-based Midwest headquarters gleams a brilliant blue inspired by Minnesota's blue skies and lakes. Find out whether the Minnesota building led to IBM's nickname "Big Blue."