Tethered: How Race and Policing Binds Minneapolis to Louisville

I stood yards from where George Floyd died when news spread about Breonna Taylor's case.

It was a sun-kissed day, and a light breeze rattled trinkets and flags at 38th and Chicago. The mood was bright. Laughter cut through the air. That all changed when we heard that the officers who shot and killed Taylor would not be charged for her death. The sun dimmed, and an eerie calm descended. I felt numb. Taylor's name seemed to jump from graffiti and murals surrounding the square. The chalked outline where Floyd died burned its image into my mind. That calm veil lifted when I was alone, and I cried. Grief and rage consumed me.

It will live as a moment captured in time for me, but not because of the case itself. My sadness was triggered by seeing the cycle of violence against Black bodies, followed by little or no accountability, continue in my home state. That same cycle stirred riots in Los Angeles when police were acquitted for beating Rodney King. It sparked protests in New York City when the cops who fired 41 shots at Amadou Diallo were acquitted, and it now brought tears to Louisville protesters who wanted someone to be held responsible.

It is a strange thing to leave one city in racial turmoil for another - to call the place where Taylor died your home, only to move where Floyd was killed. But even though Louisville and Minneapolis are hundreds of miles apart, policing data shows they share an ongoing record of unequal treatment towards people of color. And some disparities are growing.

Local experts and policy-makers say that police are not wholly to blame, but such force has eroded trust between cops and two communities strained by historical inequality. Both cities now face a call to change policing and better serve the people. For many residents, especially those in communities of color, it's a matter of life and death.

Minnesota Nice, Louisville Weird

One of the first things I noticed when moving to Minnesota was that Black residents feel under-protected and over-policed here, too. Evidence of that is in the cities' crime and punishment numbers.

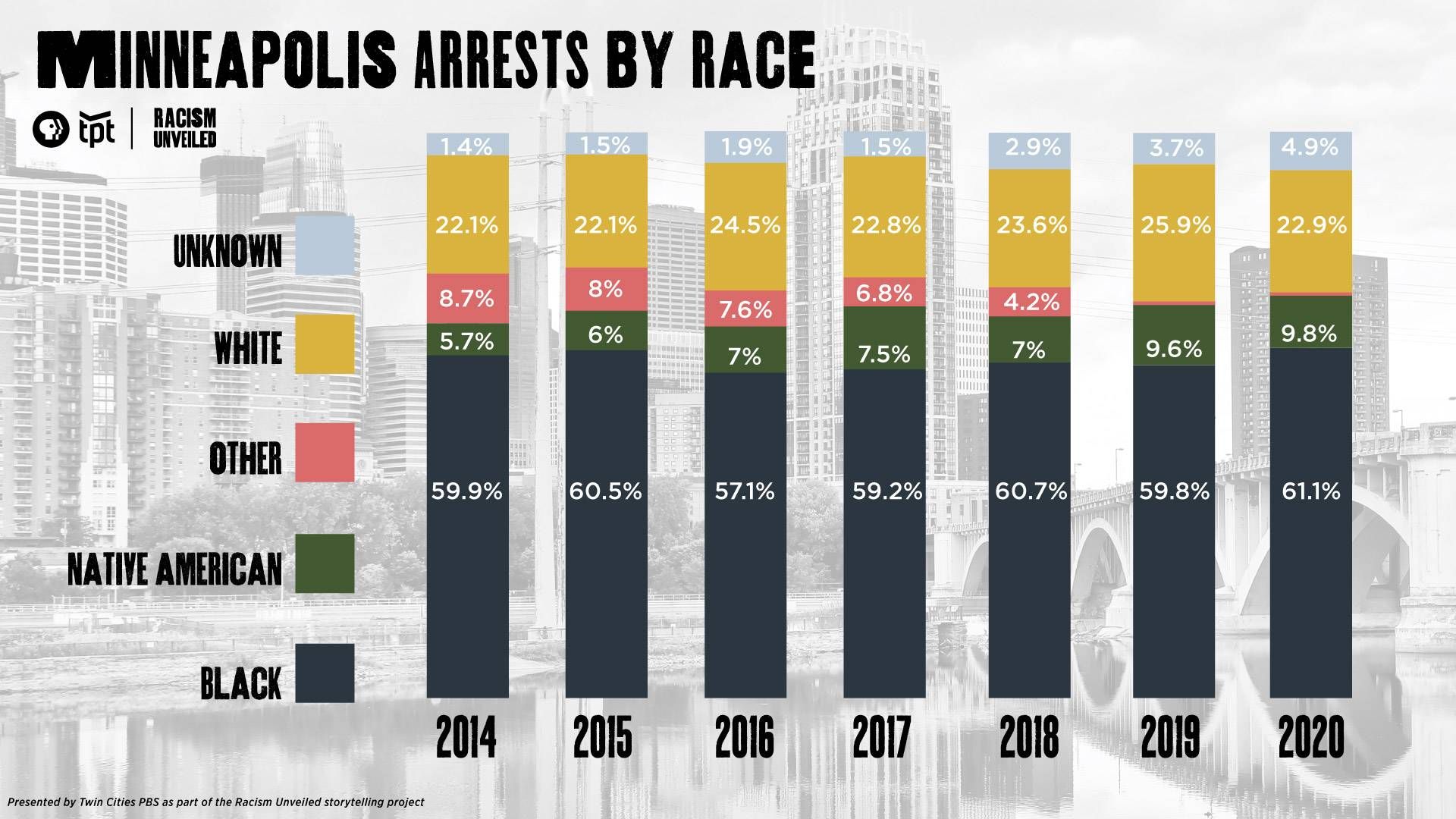

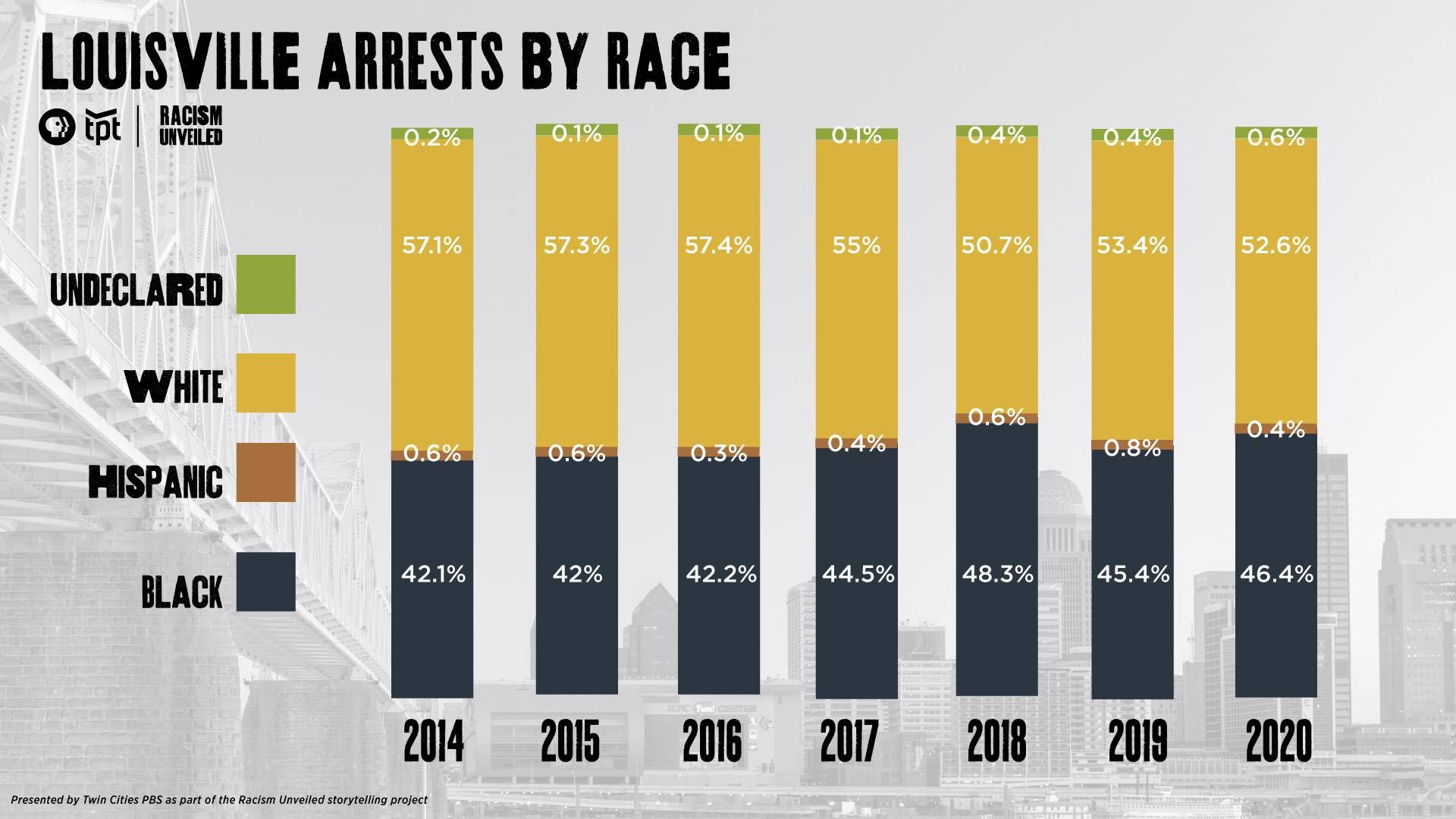

Police have arrested fewer people since 2014, the most recent year where complete data for both cities was available, but a growing percentage of those being arrested are Black - even though they make up less than a fourth of the cities' populations.

When people are arrested, the chances that force was used on them increases by race. It's a story that I've heard in conversations with Minneapolis protesters, and Louisville residents have repeated it as truth.

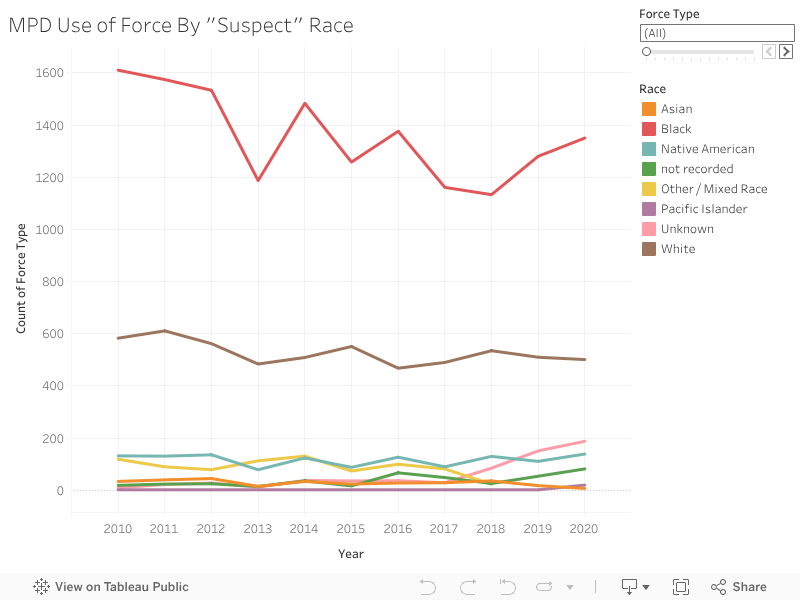

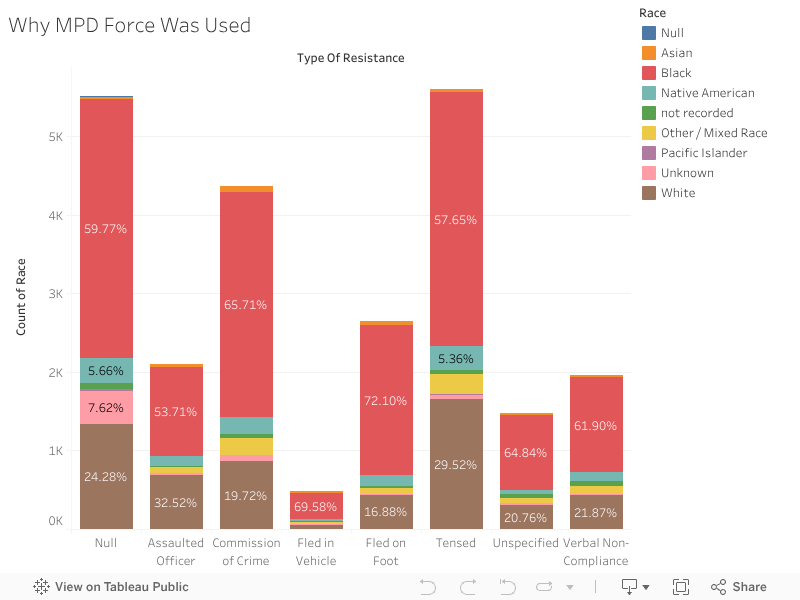

In the past decade, where full data was available, the Minneapolis Police Department has used force that includes punches, kicks, tasers, dogs and guns on more than 25,000 people. Force was used on Black people twice as often as it was on whites, and that disparity is growing. Sometimes force was used for someone assaulting a police officer, or for running away during an arrest. Most times, though, it was because they tensed up.

Fifth Ward City Council Member Jeremiah Ellison can attest to that narrative. He grew up in North Minneapolis, where a history of racist housing policies has concentrated people of color. Inspired by the example of his father, Keith Ellison, a community activist who is now the state's Attorney General, Jeremiah turned from painting murals to local government work after the police killing of Jamar Clark. Ellison said police have been a suppressive force in the community, but they seem to have had no effect on crime there.

"Traditional law enforcement, in a lot of ways, have failed communities like North Minneapolis because they don't see their role as protecting the people there," Ellison said, adding that financial strain in the community pushes some residents to illegal activities. "[If] you remove them off the street without ever addressing the underlying reason for why they are there, somebody's just going to come fill their empty slot."

City data shows that crime in neighborhoods that include North Minneapolis has increased in recent years. And a new University of Minnesota report found that North Minneapolis residents do not believe that officers respond to their concerns. Many feel that police criminalize them without solving more serious crimes. Twin Cities PBS asked the MPD multiple times to comment on this story, but none of those requests were returned at the time of this article.

Similar disparities and concerns persist in Louisville. Police data analyzed by the Root Cause Research Center shows that 61% of people shot by Louisville police since 2011 were Black. Most of those cases are still being investigated. The police department's most recent citizen attitude survey also found that Black residents were less satisfied with police than whites.

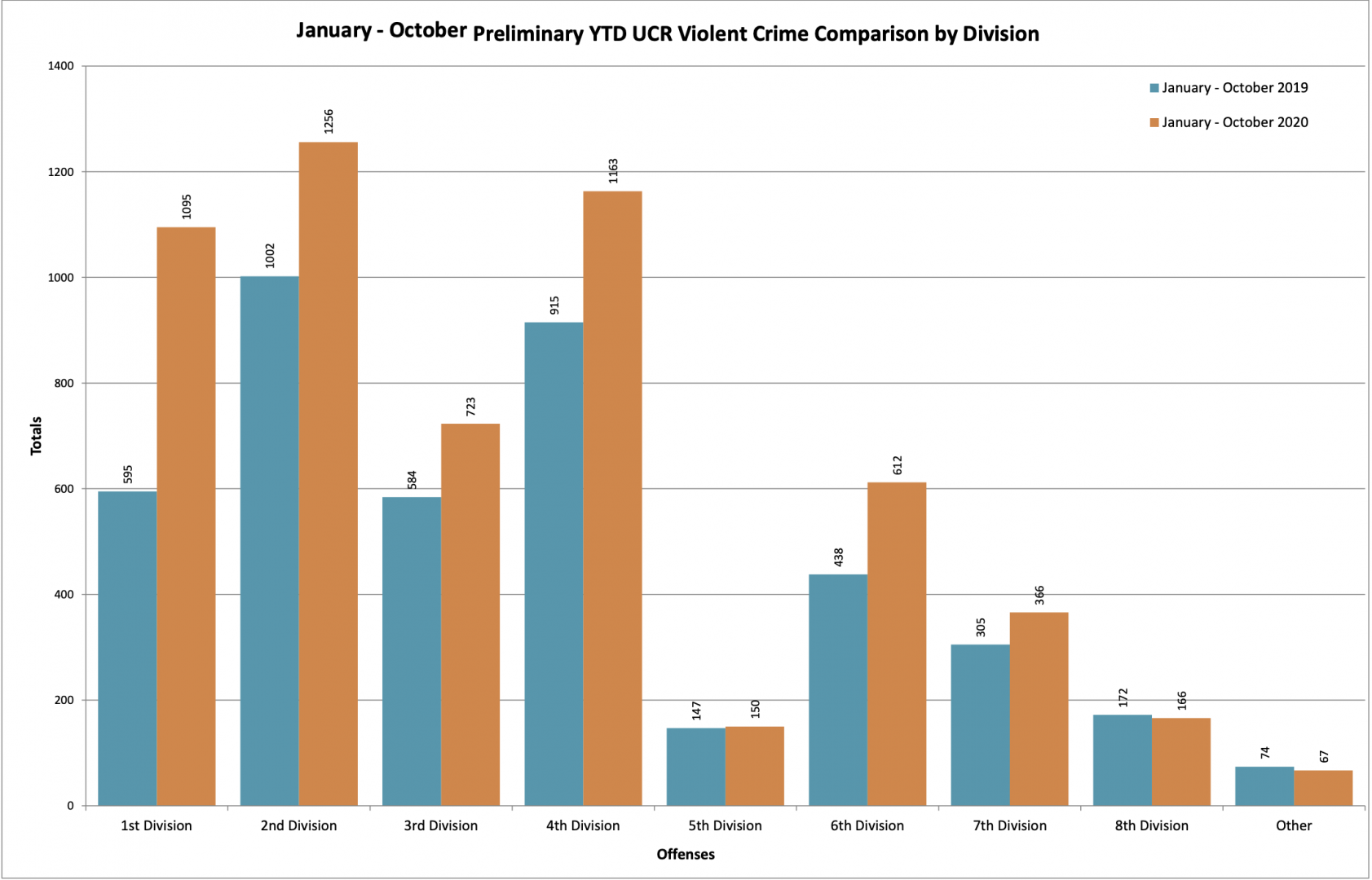

Despite such force, violent crime in the city has surged. The sharpest increase is in LMPD's 2nd division, which includes the city's urban core and most of West Louisville - an area like North Minneapolis where redlining, segregation and years of disinvestment has concentrated Black people. Louisville police data shows that the district has witnessed the most homicides this year, but just over a quarter of them have been solved.

Jasmine Martin, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology graduate student who analyzed police data for the Root Cause Research Center, said these stats on officer shootings implicate the city's entire policing network.

"This is a partial image of police violence in Louisville. It's not just LMPD killings - LMPD shooting residents and civilians - it's the entire institution of policing in Louisville. It's the way that policing is so integral to the governing of Louisville," Martin said.

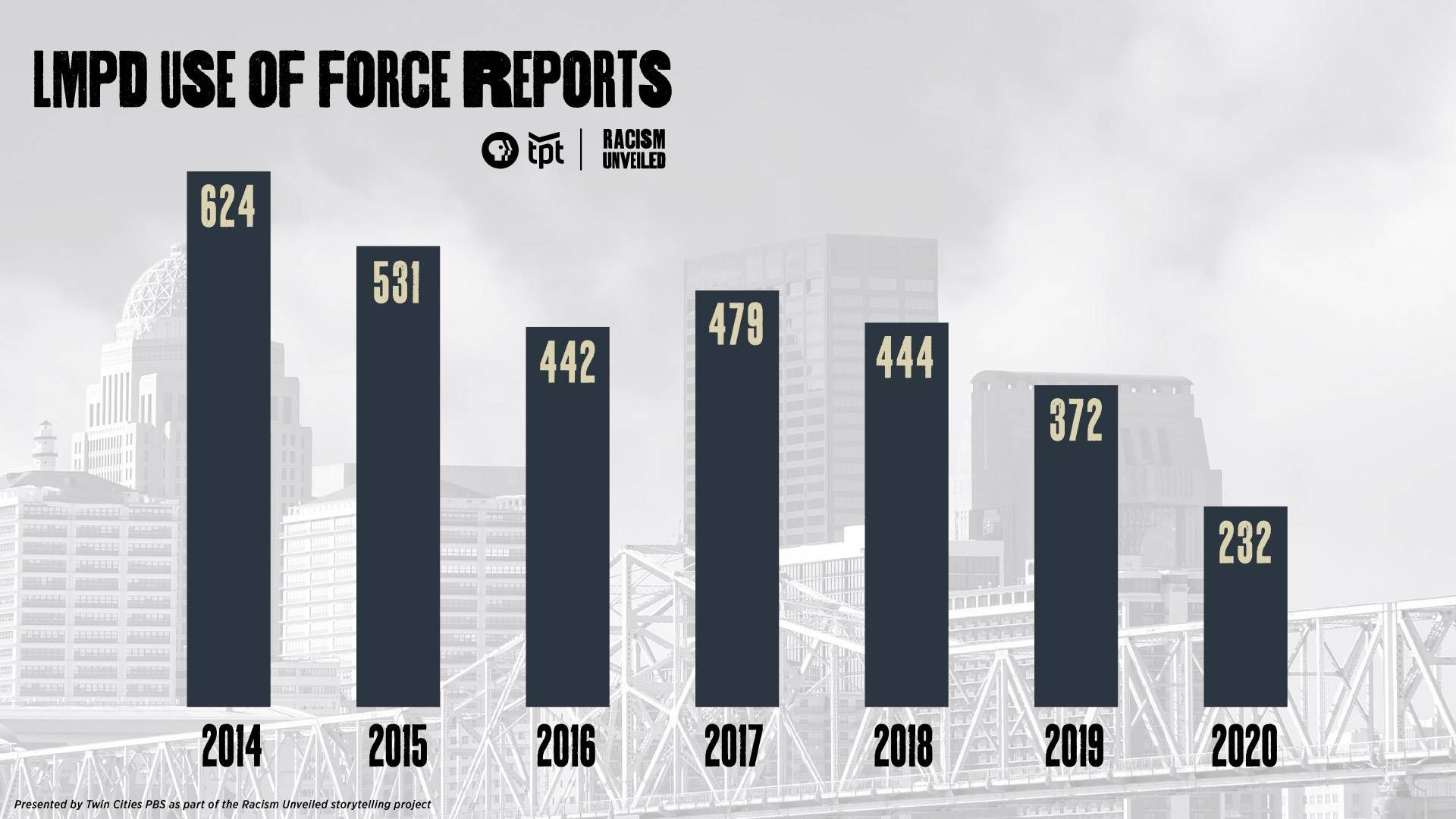

Multiple calls and emails asking LMPD to comment on this story were not returned. When Twin Cities PBS asked for more detailed data on how police use force, including the race of alleged suspects and the reason why force was used, LMPD said the information would take a year to process. A follow-up request for numbers without context was returned in three days, showing that officers have reported using less force over time.

For Jecorey Arthur, policing in the city is personal. Arthur grew up in West Louisville and was recently elected to represent his neighborhood on the city council. He said Breonna Taylor's death is part of a violent history in the city that must be addressed.

"[Police] are reactionary, they show up after something has occurred. When they show up, they are the last step to the court system or the graveyard," Arthur said. "What do we put in place to be proactive about crimes, poverty crimes, and in some cases violent crimes as well, before the police even get called?"

One proposed solution would change the roles that police have filled for years, and both Arthur and Councilman Ellison say it might work.

‘We’re at a bottomless pit.’

James Densley has studied policing for more than a decade, and is currently the chair of Metropolitan State University's School of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice. He said that police are not wholly to blame for the unequal policing and punishment of Black communities: Generations of systemic racism have pushed people of color into neighborhoods where poverty and crime can thrive. But bad police interactions have worn away residents' trust and pushed many to defend themselves.

"We've got concentrations of poverty and disadvantage and segregation and isolation and frustration, and it's all rooted in hundreds of years of US history - and the police are responding to that. Often, they're not responding very well to it," Densley said. "This reckoning right now for racial justice and against police brutality is a reminder to everybody that the police don't have the legitimacy they once had, and the community is at a point right now where they can't trust the police [and] they can't really trust what's going on in the community either."

Densley explained that police have become stopgaps for social problems as money has waned for schools, homeless shelters and mental health treatment centers. Though police are responding to those needs, many are not trained like professionals in those fields. That has created opportunities for disaster - like when Louisville police killed Darnell Wicker while responding to a domestic violence report - or when Minneapolis police killed Travis Jordan during a mental welfare call. I've seen frustration from that system motivate Louisville churches to prevent further police killings and have felt the torment it has caused in Minneapolis from stories of mental welfare checks gone wrong. Densley's solution is to put money into these public health institutions that have lost funding over time. This year, both cities have mobilized to do just that.

A new Minneapolis budget approved December 10 shifted $7.7 million from the police to public safety initiatives like a mental health crisis team and violence prevention staffers. The city also banned officers from using chokeholds. Louisville is addressing the conversation in its own way, increasing police funding, banning no-knock search warrants, and possibly allocating money towards homelessness and violence prevention. Though there is momentum for reform, Councilmen Ellison and Arthur doubt that such enthusiasm will hold.

Ellison said calls to defund the police were met with claims that such moves show a lack of care for crime victims. The growth in violence has pushed many to call for more policing, and he worries that fellow council members will retract on the work they have done.

"I fear sometimes that we are losing sight of that urgency and that I might have some colleagues who are telling themselves, 'Maybe the George Floyd situation wasn't that bad. Maybe it was just one bad apple,'" Ellison said. "We've seen Mike Brown and Freddie Gray and Sandra Bland and Breonna Taylor … there are names I've known and forgotten when it comes to Black people in the last six years who have been murdered by police, and we talk about reform every single time."

Arthur said that reparations are key to preventing poverty crimes and transforming the communities of American Descendants of Slavery, but he believes that few residents would support it.

"It removes the core of that struggle, which is the lack of wealth and ownership and opportunity, and it creates it for a class of people who built this country," Arthur said. "We've already fallen off the cliff of America, but now we're at a bottomless pit. Without reparations, without atonement for what we've gone through and what we're owed today, we will cease to exist in the very country that we built."

To me, that threat of ceasing to exist creates more urgency to find solutions for racism and policing issues in America. That urgency, and the faults and concerns raised in this article, are made clear by the death of Ki'Anthony Tyus.

We will never know Ki’Anthony's potential.

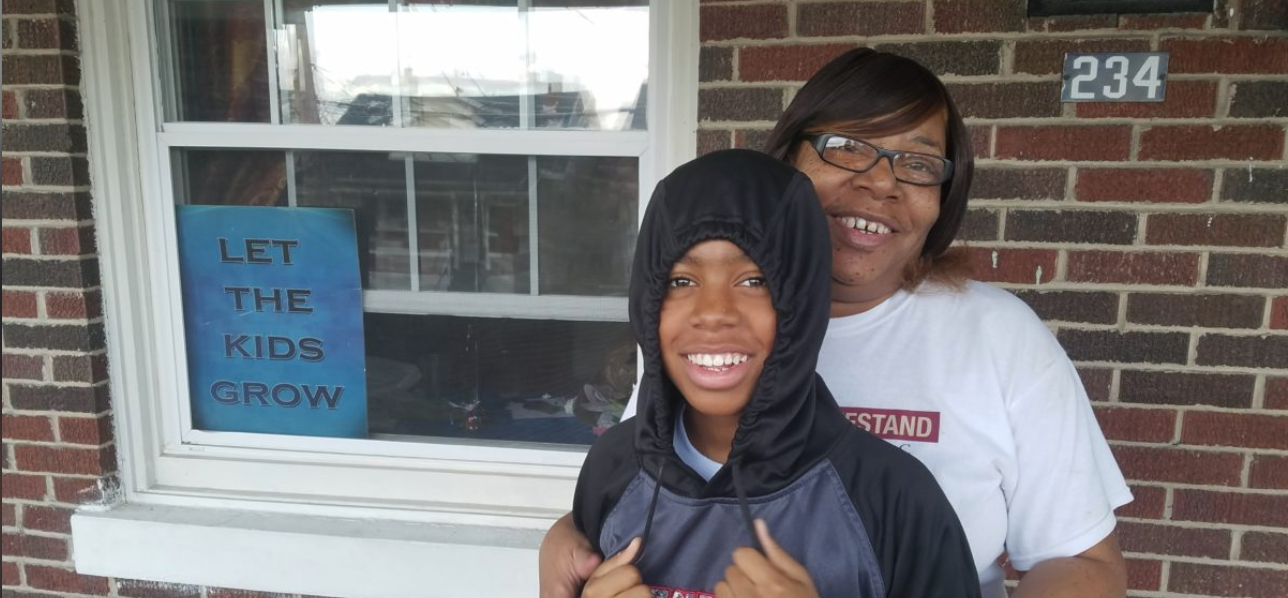

Two years ago, I walked into a white, stone house off a quiet Louisville street, to meet a kid named Ki'Anthony Tyus. The last time we talked, Tyus' feet dangled inches from the floor but swung back and forth with the carelessness of a teen. His face was soft, but beamed with excitement when he daydreamed about playing basketball with Kyrie Irving. He reminded me so much of my cousins, yet he had been through unimaginable trauma.

Like a lot of youth in the area, unchecked violence struck Ki'Anthony in a drive-by shooting. It shattered his femur bone at the age of 9. The suspect was still on the loose after his shooting, and detectives said no potential witnesses were coming forward. Professor Densley said that happens when communities no longer trust the police. Tyus worked as a gun violence activist before showing signs of trauma, acting out in school and getting into trouble. His grandmother intervened by scheduling a therapist to see him during Christmas week. Before that session happened, Ki'Anthony fell victim to over-policing that has killed many in America. He got into a friend's SUV that turned out to be stolen, and the police chased them. The SUV flipped over during the chase, killing Ki'Anthony at 13 years old.

I think about him a lot. I consider the lost potential that the world will never see because conditions surrounding the community killed him. I think of his family, traumatized by the loss of their grandson, cousin and brother who would sometimes film himself dancing in church. And I saw his face in Cortez Williams, Jamontae Welch and Demetrius Dobbins: three Minneapolis teens who died this year in a similar police chase.

Whatever solution the cities find, all eyes are on Minneapolis and Louisville. What happens next could pave the way toward more equitable policing, or continue a cycle that has claimed the lives of too many George Floyds, Breonna Taylors and Ki'Anthony Tyus' whose dreams were cut short.

This story is part of the digital storytelling project Racism Unveiled, which is funded by a grant from the Otto Bremer Trust.

A surge of minority voices has responded to the police killing of George Floyd. In the weeks since Floyd uttered, "I can't breathe," as ex-Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin pressed down on his neck, a new collective of individuals is taking action by running for office, engaging in politics and stirring change among youth. But is the momentum a movement or a moment?

"Mementos of civil unrest pepper the walls of buildings and storefronts. Plywood boards still cover broken windows of some shops. Signs reading "George Floyd" and "Black Lives Matter" are spray-painted across Lake Street. A database at the University of St. Thomas has catalogued more than 1,300 similar graffiti and murals in each U.S. state and 76 countries. There are fewer protests, but more tense moments like that traffic stop." Data Reporter Kyeland Jackson offers this dispatch on the aftermath of George Floyd's police killing in May 2020.

Saint Paul's neighborhoods of color have a disproportionate number of vacant buildings than areas primarily occupied by white residents. That fact has a direct impact on crime rates, public-health risks and quality of life. Data reporter Kyeland Jackson examines the links between vacant properties and the city's racial disparities.