Should Cops and Corporations Be at Pride?

A look at Pride's history and its roots in anti-police brutality.

Every June, Twin Cities Pride organizes a parade - one of the largest Pride festivals in the nation - to celebrate the LGBTQ+ community. As a celebration in the streets where people can feel free and safe to authentically be themselves, the event marks how far the LGBTQ+ movement has come. But not all members of the community see themselves reflected in Pride or see the event as safe.

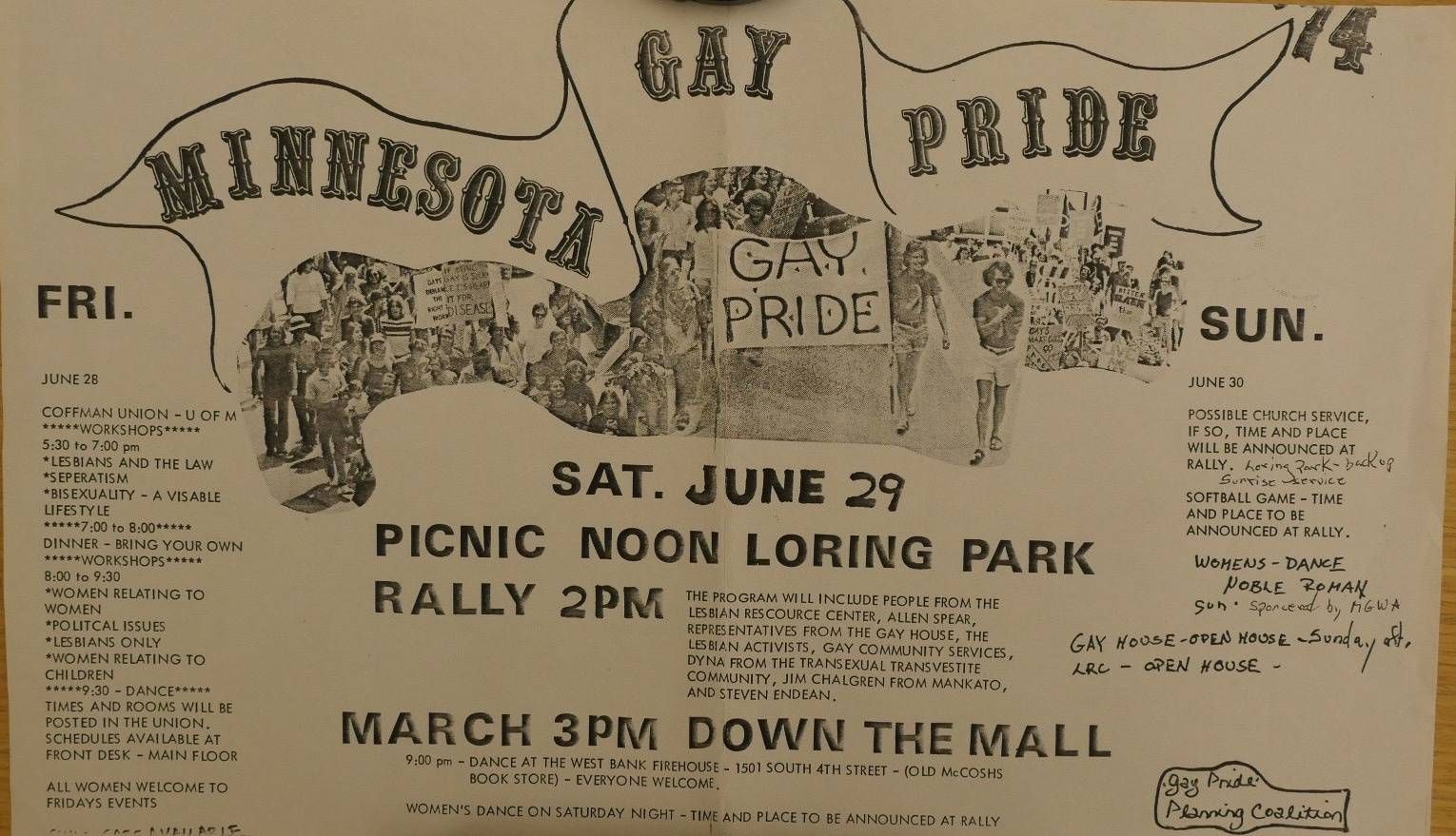

Many point back to the Stonewall Uprising as the flash point of the LGBTQ+ movement and Pride. On June 28, 1968, police raided the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City that was frequented by LGBTQ+ people of color. The raid turned violent, and out of the many who fought the police and protested during the six day uprising that resulted, two transgender women of color emerged as the leaders of the uprising, Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera. The following year, there was a march to commemorate what had happened and protest homophobic sentiments, as well as police brutality toward the community.

Across the country today, that march has turned into a parade with corporate floats, police and what some have described as a predominately white, cis-gender crowd. Activists across the country and in the Twin Cities are actively pushing to not only keep Pride a celebration, but to remember its history, its Black and brown founders, and the politics that ignited it.

‘Part of a community that doesn’t always respect me’

In 2017, Andrea Jenkins became the first African-American, openly transgender woman in the country to be elected to office. Jenkins represents Ward 8 and is Vice President for the Minneapolis City Council.

From 2015 to 2018, Jenkins worked as a curator for the Tretter Transgender Oral History Project at the University of Minnesota. She's sat down with almost 200 transgender and gender non-conforming people across the Upper Midwest to document their stories and experiences.

Jenkins came to the Twin Cities from Chicago in the late 70s as a college student. At that point, the term transgender wasn't commonly used - it didn't gain traction until the mid-'90s. When she arrived in the Twin Cities, she explored her sexuality as a Black man.

"I certainly knew in my own head that I was trans, but I wasn't out. I wasn't open about my gender identity to anyone, barely to myself," Jenkins said.

"I experienced racism. A lot of white gay males either exploited Black people, and sort of fetishized or objectified Black bodies or completely rejected Black people all together in relationships, in social situations, etc. But for the most part, I found acceptance in the Black, gay community."

When Jenkins decided to come out in the '90s, she was rejected by the community she found in the Twin Cities. Even her closest friends shunned her.

Jenkins said that her experience isn't unique. Trans women, particularly Black trans women, have struggled to be recognized and respected by the larger community, despite the fact that they've been leaders in the LGBTQ+ liberation movement. This is part of the reason why Jenkins describes Pride as a complicated experience for her.

"I'm 6'2" tall. I stand out. A gay man, people don't necessarily know that they are gay. … Trans people stand out, and so if you want to have any kind of retaliation against gay people, you strike out at the people who you can see and recognize, and that's historically been trans people. So, Pride is loaded for me," she said. "I feel very much a part of a community that doesn't always respect me and honor me as an individual."

‘Pride doesn’t reflect me’

In 2016, Taking Back Pride interrupted the Twin Cities Pride parade. A BIPOC LGBTQ+ led march, Taking Back Pride was started by the Twin Cities Coalition for Justice For Jamar (TCC4J), a community group created in 2015 after police shot and killed Jamar Clark, a 24-year-old Black man. The coalition, which additionally organizes protests and supports the families of victims of police shootings in the Twin Cities, felt that Twin Cities Pride was not a real reflection of the LGBTQ+ community. Instead, they argued that Pride ignored the history of the movement, which is rooted in anti-police brutality and anti-capitalism.

"For a lot of queer folks in the cities after Jamar was killed and other police murders, having cops at the Pride celebration was really kind of a slap in the face," said Jae Yates, an organizer for TCC4J and a prominent voice in the Twin Cities around anti-police brutality.

"[TC Pride is] mostly organized by white people, and they are not cognizant of the fact that there are Black queer people who want to come to Pride and feel like it's an environment that they're not just retraumatizing themselves by going to. A lot of Black folks have direct experience with police brutality, it's not a hypothetical."

When Yates moved to the Twin Cities in 2016, they were disappointed with the inauthenticity of the corporate floats at Pride.

"I was like, 'This is not what I want to participate in.' I know the history of Pride, and I want a Pride that reflects us and our actual community, not leeches that are trying to profit off of us."

Growing up in a small town in Iowa, Yates and their friends frequented the only queer bar in a 50-mile radius. Every June, when Pride rolled around, Yates celebrated in Cedar Falls. The stalls of queer-owned businesses, the crafts and the music - it was small, but it was something that felt like it was for them.

When Taking Back Pride interrupted that parade in 2016, Yates found the type of political march they were seeking. They've participated in Taking Back Pride every year since.

"Black and brown, working-class, queer people are not interested in assimilation. It's not really about being accepted by the wider capitalist culture. It's about being counter to it, and it's about fighting against it and fighting against oppression," Yates said.

Cops and corporations at Pride

Activists like Yates say their work is unfinished. While the community's efforts led to some changes like the Power to the People performance stage at Pride, TCC4J is demanding that the police no longer be a part of Pride due to the continued criminalization of transgender and gender non-conforming people.

Former Police Chief Janee Harteau, Minneapolis' first openly gay police leader, and other LGBTQ+ officers have publicly expressed feeling hurt when they were asked not to be present or keep a low profile at Pride. While Jenkins was sympathetic to that, Yates believes they've chosen a job that is fundamentally at odds with the LGBTQ+ movement.

"They are still the people that are oppressing us," Yates said. "They've decided to take a job that requires them to oppress the communities that they're from."

Jenkins explained how police have historically had a negative impact on trans life, specifically.

"Trans people have been criminalized all throughout society. It was literally against the law to wear more than three articles of the opposite [gender's clothing] - you could go to jail for that in many, many, many places, including New York City," Jenkins said.

"Up to this day, it's illegal to go to the bathroom in some places for trans people," she added.

If Pride is only a celebration and doesn't call out continuing forms of oppression, then it is losing sight of its roots, Yates said.

"We're trying to both educate people about our history and get people to understand that just because we got marriage equality and just because a couple of states have improved healthcare access for trans people - all those things are good, but the fight is absolutely not over," Yates said.