Muralist Cadex Herrera Portrayed George Floyd 'As a Person of Light'

The artist behind one of the most iconic George Floyd murals discusses how street art can spur conversation about race and justice.

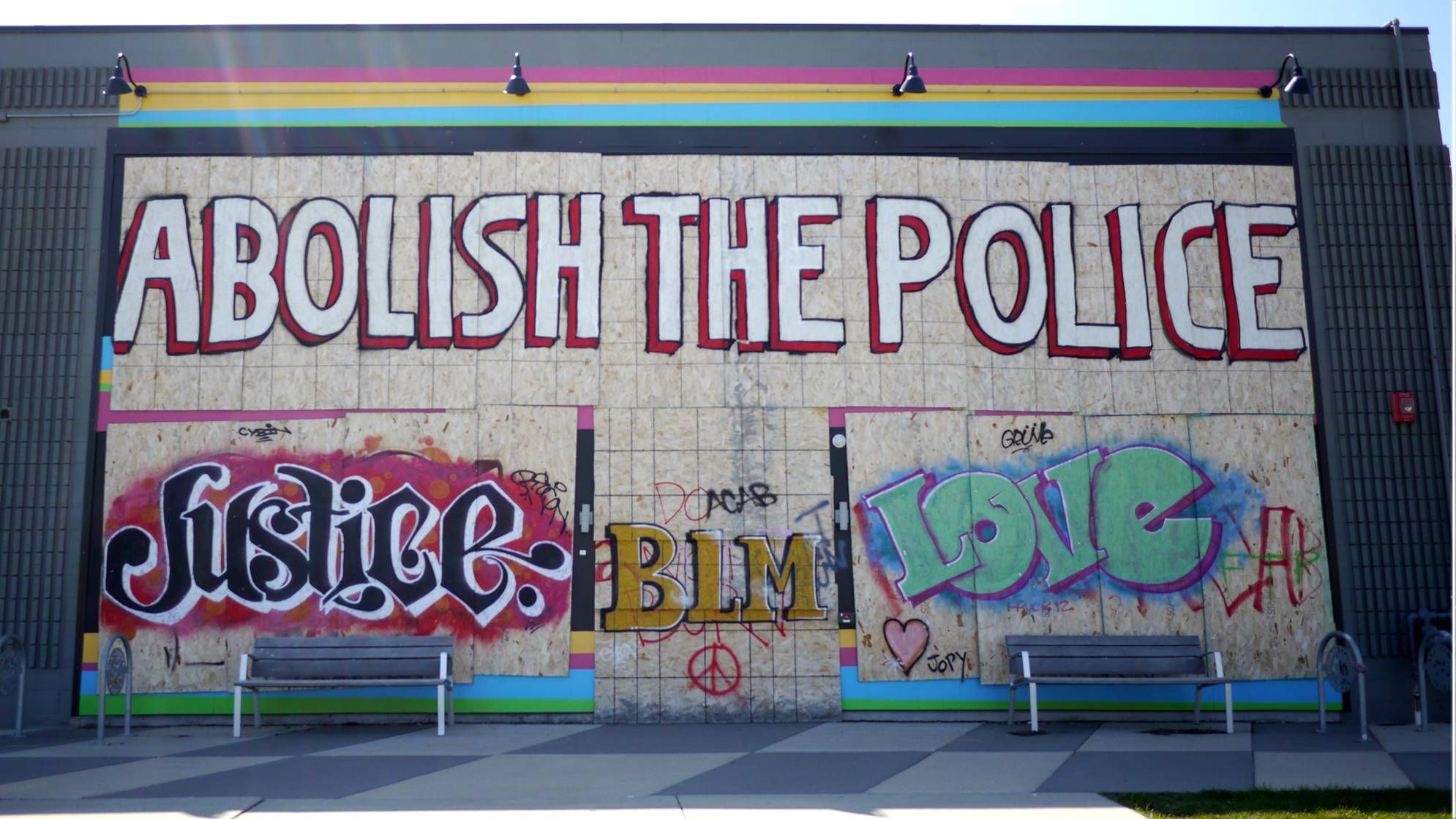

Walk down the streets of Minneapolis and you'll notice that the view has changed a bit. Store exteriors, previously plain brick-and-mortar or concrete, are now full of artistic messages, sharing community hope and wisdom.

An artistic movement that began in Mexico in the 1920s, muralism is characterized by large-scale murals centering social and political themes - and while the art form is not new to Minneapolis, it has taken on a noticeably different feel over the last year.

As the George Floyd uprising shifted attention to social justice issues, the art in our communities shifted with it. The murals that now line the streets of Minneapolis are colorful and distinct, created by professional visual artists and community members, alike, some on display here in the interspersed photographs.

Street art has been here to remind us that Minneapolis demands justice — and that art through community does have power.

A striking portrait of Floyd in front of a vibrant yellow sunflower quickly became a symbol during the uprising. Painted by Cadex Herrera, Xena Goldman and Greta McClain, the mural is located at the site of the murder, where many have since come to pay their respects.

I spoke with Herrera to learn more about the creation of this now iconic image and how street art is becoming a more acceptable art form for social justice artists.

The following excerpts of our conversation have been edited for clarity and length.

Tell me about yourself and how you got involved in the Minnesota art community.

I'm originally from Belize, Central America. I've always been interested in art, it's something that I just learned to do since the first time I picked up a pencil. It was a way for me to find peace. I had a really tough life, [and] art was a way for me to deal with the trauma and life situations that were happening around me.

My work with social justice issues began about five years ago when I first got my Instagram account. I was an art educator at Creative Arts Secondary School in Saint Paul. One of the ways I wanted to reach out to my students was to show them that you didn't need to have expensive equipment to be an artist — you can show your art on all these applications. As a way of encouraging them to do that, I started posting my work.

That grew into me creating very focused work on the different issues that were happening in this country, as well as around the world. This had me focus on the idea that I could use my art as a teaching tool, as a way to open the conversation about race, justice, immigration and marginalized people, and bring them to the forefront.

How did the mural come together and how has making this mural affected your life over the uprising?

Initially Xena Goldman and Greta McClain came together. I had a connection to Xena Goldman through CLUES, Comunidades Latinas Unidas en Servicio. She was another artist in the mural apprenticeship program, and she invited me to design something for the wall at Cup Foods. There had been previous murders of Black men, brown men and women in the news prior to George Floyd, and every time something like that happened, I would create a portrait of that person along with either phrases or a song that spoke against that idea of police brutality. My work was already in that vein and involved in that.

Making the mural was so full of emotion, of anxiety, of anger, but at the same time there was this feeling of hope just because of the people who were gathered here and were making speeches about challenging the system and demanding justice — it gave me a lot of energy as an artist and a human being. It became almost a spiritual and out-of-body experience. I just felt like I was just floating in air and just working.

The very next day, media organizations are picking it up and all of a sudden it sort of spreads around the world, and there's folks from different parts of the world using the idea of the sunflower and George Floyd, and they're creating their own George Floyd murals as well, which to me was the most amazing thing.

What was your thought process for creating the design for the Cup Foods mural?

I knew there were very specific things I needed to put into the piece. One of them is, any time they show any person of color, the media has a way of portraying them in an incredibly negative way. Recently, this young man in Chicago, Adam Toledo, the first thing you start seeing on the media are them holding guns up or putting up the middle finger or having money in their hand — these are all sort of negative portrayals of a person. That's one of the things I wanted to address. I wanted to portray George Floyd in a positive way, as a person of light, as a person of multiple colors and energy coming from him, an almost spiritual being.

The second thing I wanted to address was that I needed his name to be strong and powerful. The idea was that, if you saw his name, it would be readily identifiable and it would give you that sense of strength and solid letter forms and sort of golden colors, again to accentuate the idea of positivity. I needed his name to be remembered, as well as their names behind him, you know — say their names.

At the bottom of the mural, you can see the words "I can breathe now." Initially we did not have a plan for this specific part. There's this lady who came to visit us very early in the process. When I explained to her what we were doing and I told her we were going to write George Floyd's last words at the bottom, she said, "Why don't you guys do 'I can breathe now, because by putting up his image on that wall you've released him." And that was incredibly powerful to hear from a community member, and it made so much sense.

There's been some critique of the mural, taking issue that neither you nor Goldman or McClain identity as Black. What do you say to those people?

I am incredibly grateful and honored to have worked with the artists that were involved in the creation of the mural. Xena Goldman and Greta McClain were instrumental in the creation of the mural.

Although we were the primary artists, there was involvement from artists that were passing by and decided to help, as well as community members that were gathered and wanted to add to the mural. I would like to stress that that day, Black, Muslim, Latinos, Indigenous, Hmong, young, old; anyone who wanted to participate was welcomed and encouraged to paint with us. And they did.

In no time in my life have I had to justify who I am as a human being as I had to do in the last year. Imagine, being asked what my race is, and that being the basis if you are accepted or not. But this is America after all, and if there is one true thing about this country is that you are measured and judged by your race. So to answer the question, I am not white, my racial background is, on my mother's side, grandmother (Spanish Mestiza), grandfather (Kechi Maya). On my father's side, grandfather (Mopan Maya), grandmother (African). In Belize, I am Mestizo, Indigenous, Spanish, Black. In America, I am Hispanic.

You have made murals in your past, how has making murals in Minnesota felt different in the current environment, and how have you felt that street art has changed for you and other artists over the years?

This is technically my first official mural here. As an artist I think that street art — muralismo, muralism — has come a long way, but I don't think has gone far enough as far as being an acceptable way to express oneself, to give somewhere a sense of time and place, to bring communities together. I think that there's still this notion that a neighborhood and walls should be the color of brick and Minnesota's famous for their off-white and yellow tones on pretty much all the buildings.

I think there is a lot of space for people to start accepting that public art should be a part of any community. Artists and their visions should have places where they have permission to express themselves and be creative, where they have permission to give whatever place they're in a sense of community — through art that talks about that community, that talks about what's happening in those communities, that talks about the connections and diversity that exists in that community, and I think that muralism can do that.

What is your hope for the future of Minneapolis street art and the future of Minneapolis in general?

I hope that the people in charge, the people at the top, can start thinking in a community sense — of creating resources not only for artists but for communities to be creative in different ways. Not just street art, but music and literature and poetry and dance, it's all part of the culture and the community; this makes any community a much richer place.

I feel that there [aren't] enough places to go [where] this exists — so let's say that you want to get together with artists, there isn't a place in the city where you can go meet up. There are different organizations that provide some resources, but it's not always easy to get in for various reasons.

My dream is that the folks that are on top that make these decisions can start providing those spaces for artists to participate. They should be community-driven and available and accessible to everyone — where everyone's welcome and accepted. It should be part of any community to have a space where creative folks can get together and feel like they are accepted, and they can create and feel like their voices are being heard.

How do you think art can address social justice issues? What is the wisdom you can offer to other people who want to make social justice art?

First off, look around you — what's affecting your life? What's affecting people in your community? How are you using your art to speak to that? It doesn't have to be complicated, it doesn't have to be perfect. What is important is the message. Not only that, but you have to stick with it and keep repeating yourself in a way that's creative and interesting, because you don't want to lose people's interest either.

I think that if it's not for artists who speak out, we wouldn't see that part of art. When we go to a museum, we see something beautiful like landscapes, flowers, and it's all right, it's an incredible thing, it's incredibly beautiful. But I think that artists have the power to use those skills to speak truth to power, to say, "Hey, this is what is happening in my life from my point of view, from my perspective."

Sometimes the things that you are saying, not everyone agrees with it. You have to be okay with knowing there's going to be blow back. And you have to be okay with the idea that everything you say is not going to be accepted by everyone. You have to make a commitment to it. You have to stand by your vision and your work and your words because the second that you back away, your voice loses that power.

This story is part of the digital storytelling project Racism Unveiled, which is funded by grants from the Otto Bremer Trust and HealthPartners.

In the wake of George Floyd's 2020 murder, artists have seized on the moment to create art that shouts for social justice - while others in the community are working on innovative ways to preserve that art. Meet two local women who are bringing healing and empowerment to Minneapolis.

In April 2021, former MPD Officer Derek Chauvin was found guilty on all three counts for murdering George Floyd. But the road ahead to lasting change in the systems and structures rooted in racial inequity remains long and winding. In this episode of Trial & Tribulation: Racism and Justice in Minnesota, five experts answer the question, "Where do we go from here?"

Craving new routes for your daily walks? Both Minneapolis and Saint Paul feature "outdoor galleries" of vibrant murals – many of which reveal social justice themes – that might just fulfill your hunger for beauty and meaning in these turbulent times. Your mural walking tours in Minneapolis and in Saint Paul await, complete with maps for easy navigation.