Leading Through the Pandemic: Pinewood Elementary Principal Andrew Skinner

“Leading Through the Pandemic” is a series focused on Twin Cities leaders and their reflections on the year of living during a pandemic and leading their teams into new ways of working.

In April 2021, we spoke with six Twin Cities leaders from various sectors – health care, independent business, nonprofit organizations, and education and religious institutions – about their experiences in decision-making, staff management and service to their audiences, patients and members during the last year of COVID-19 and civil unrest. Without a doubt, 2020 tossed countless challenges at any semblance of stability, but the topsy-turvy year also inspired these leaders’ renewed hopes for a more sustainable future, one they might not have imagined without first grappling with so much unexpected turbulence.

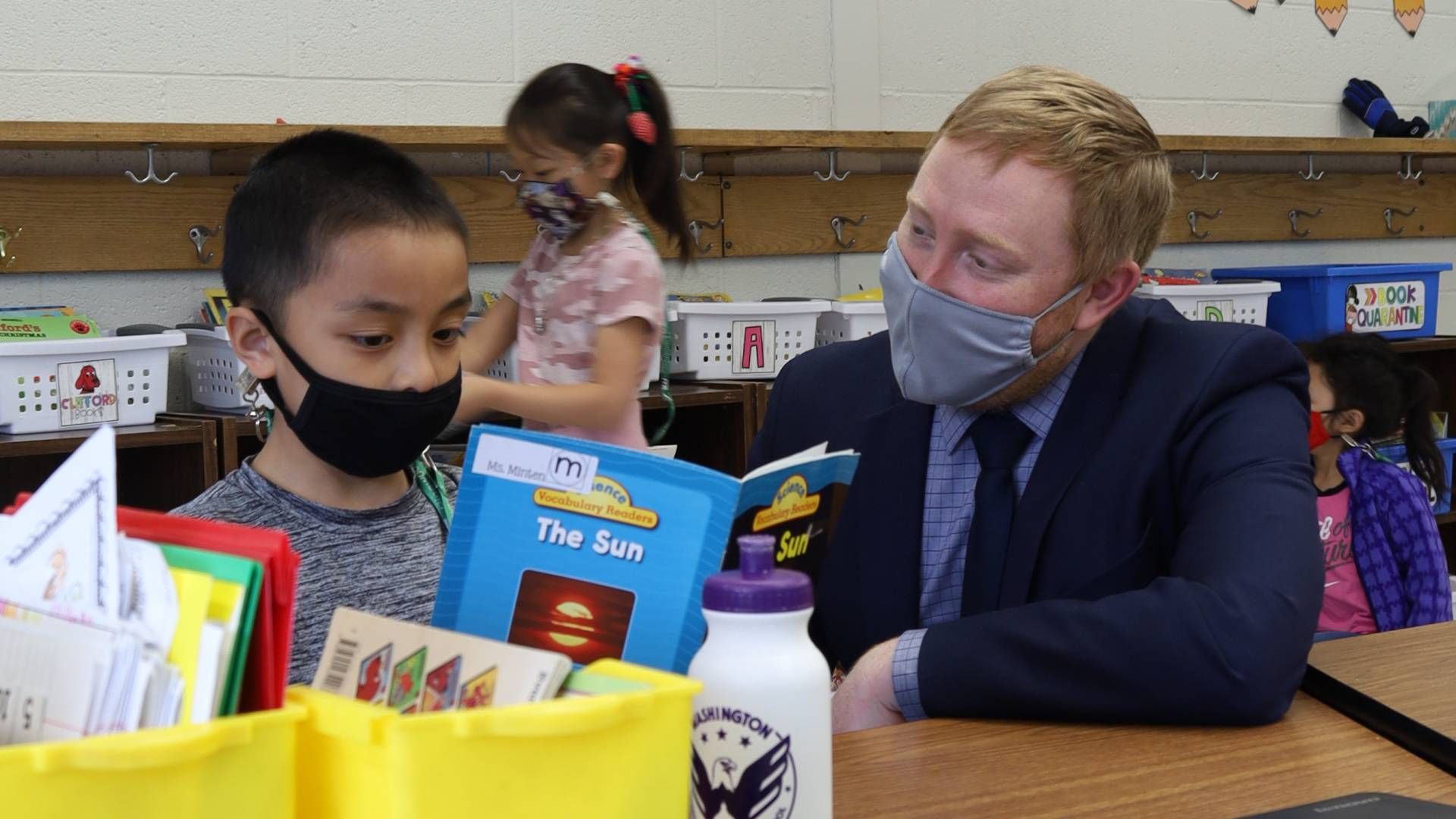

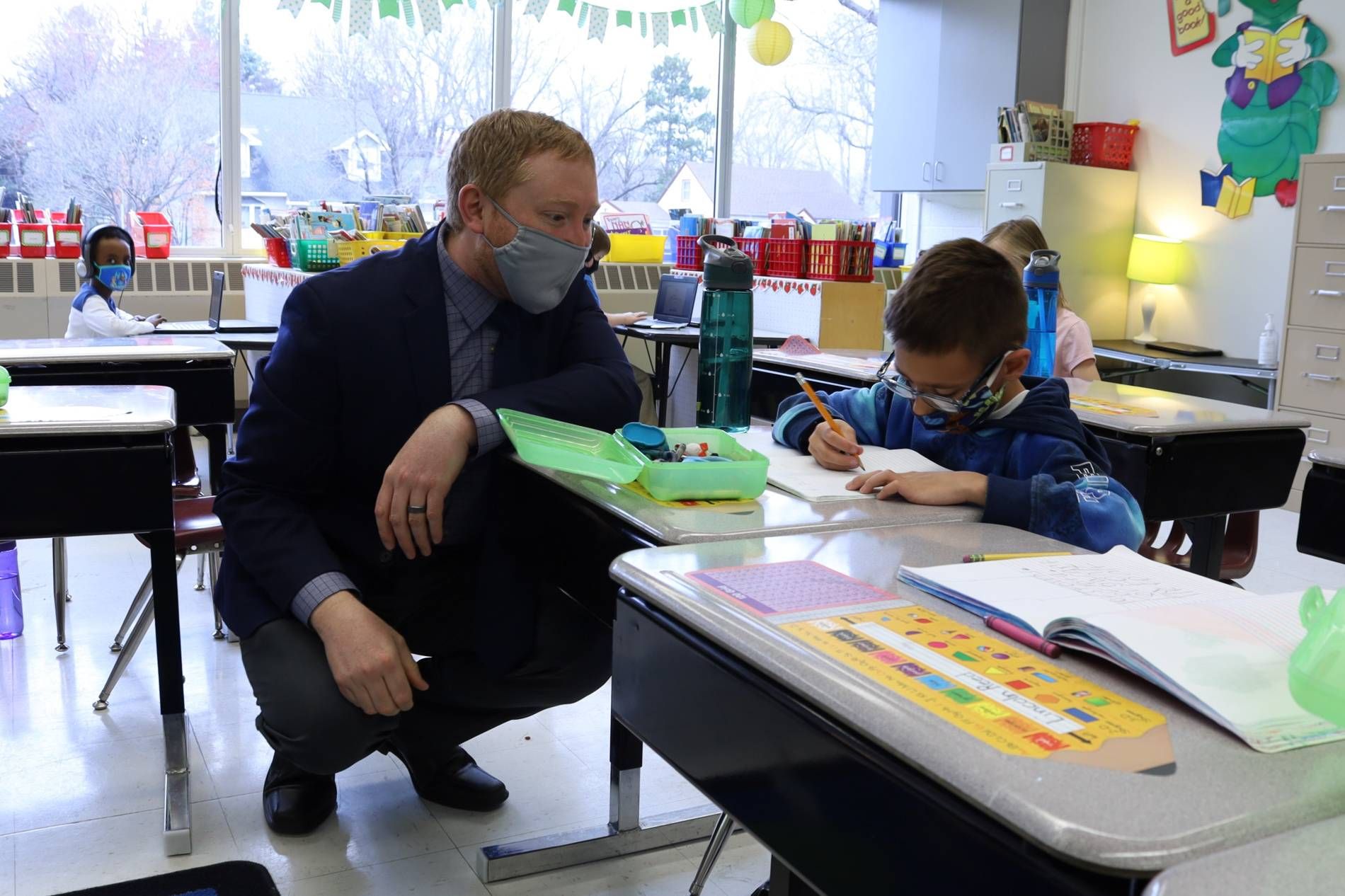

Andrew Skinner proudly serves as principal at Pinewood Elementary School in Mounds View, Minn., with 540 students in grades 1 through 5 (53% are students of color) and 42 staff. After beginning his career teaching English at the middle level, he has served as both an elementary and middle school administrator in the Mounds View School district since 2012. In his fifth year as principal, he recognizes the need for educators to work smarter, not simply harder, in the pursuit of adequate and equitable systems of support for each child. As a lead learner in his building, he is highly dedicated to the continuous improvement of our educational systems, and seeks to improve how we navigate and remove systemic barriers for students.

In his own words, he describes the obstacles, successes and opportunities for experimentation presented by the last year.

THE WAYS SCHOOL HAS CHANGED DURING THE PANDEMIC

This year, we are now fully open to families who are choosing in-person learning, but we also serve a third of our population through distance learning. Volunteers are not allowed in the building this year, and the office is open to limited visitors with screening protocols in place.

Due to Governor Walz’s order, classrooms at the elementary level do not need to adhere to social distancing, but we are doing what we can to create as much space as possible between students. Students are in pods, meaning they do not mix with students from other classrooms during class time, lunch or recess time.

Since September, our building has transitioned from distance learning to hybrid learning, back to distance learning, and again to full in-person learning.

LOOKING BACK TO MARCH 2020: HOW WILL WE MANAGE?

Our biggest questions were: How are students going to be able to learn from home? And, how long is this really going to last?

Addressing the anxieties and uncertainties and normalizing them for staff were critical in getting to the actual work of pivoting to a completely new model. Letting staff know that this is not forever and emphasizing, “We’ve got this!’ were first steps.

Once we realized it was going to be longer than the spring of 2020, there was some grieving. We grieved what we saw as the loss of serving our students and families at the high levels we were used to. We worked on a shift in mindset like never before. We had to fundamentally change overnight. We quickly learned Zoom, Seesaw and other technology tools in order to best engage students to keep them academically and socially connected.

From that first distance learning in the spring of 2020, we knew students couldn’t be on a screen all day. If adults can barely stand it, how can we be doing that to our kids? We needed to create a system of assembling and distributing physical materials so students could have access to hands-on materials, like learning kits with math manipulatives, physical books, art supplies and more.

Meals were another hurdle: How were we going to feed our students? First, we utilized the bus company to create stops for food distribution and then eventually moved to pick-up sites, but kept delivering to families who had no transportation to access the food at central sites. Our food service group completely changed their model from hot lunch to pre-packaged meals with instructions, almost like an elementary version of Blue Apron.

NAMING THE PROBLEMS FIRST, THEN DEALING WITH THEM

The biggest hurdle for me and my staff was the amount of high-stakes communication coming through the pipeline. We live in an age of change, but with COVID, things changed constantly and fast. There was a race for information. Oftentimes, we were only hours ahead of any state and federal guidance, which changed almost daily. As a school, we were not used to providing so much new information about such rapid organizational change. School had essentially been the same year-to-year, and our regular communications had included some updates, tweaks and announcements. With so much coming at us, we decided to use Google Docs and simply highlighted each update every time it was shared out. It seems a bit low-tech by today’s standards with Slack, etc., but it got the job of communication done.

I also held weekly update meetings with staff over Zoom, not just to share information, but to be open to listening and sharing stories of anxieties and worries. Sometimes, I didn’t have much, but coming together was still appreciated, and our staff would ask amazing questions we needed to hear and address to move forward. We emphasized “Naming It” -naming the blind spots and then following through.

THE PANDEMIC PUT THE SPOTLIGHT ON THE REALITIES OF FAMILIES IN NEED

This experience has put an even bigger spotlight on the inequities in our systems. Access to food, internet and transportation have never been more a part of our work.

The pandemic has not only technically changed how schools work, but it’s changed our mindset around our roles as educators. Our teachers and support staff were able to get a much better understanding of the reality of our families, and the supports and barriers they have. We’ve been able to focus on what really matters. For instance, I don’t think we will look at homework the same way ever again, as we’ve gotten a view into the lives of our families, and seen for ourselves how challenging and sometimes harmful some of that work can be, especially during a crisis. Families are doing the very best they can, and we owe it to them to partner in a way that doesn’t put undue burdens on them during this time.

Another obvious leadership challenge is that, as educators, we are not virologists or epidemiologists. With so much uncertainty, we were hearing about different pathways forward in re-opening schools. Do we need to sanitize surfaces? Is the ventilation effective and how do we know? What type of air filtration are we using? Do students wear masks outside? We have had to be honest and okay with saying, “We just don’t know right now.”

As leaders, we need to acknowledge when we don't know something. Everyone wants a clear, definitive answer, and it feels good to give them that, but it is not the right thing to do if we aren’t sure ourselves. I have been challenging myself and my staff to “live in the gray,” which is easier said than done, especially with anxieties so high. With so many streams of contradicting information and strong opinions, it’s been important to stick with what we know while acknowledging things can and probably will change.

Finally, the challenge of re-opening schools has brought up the question of: What if a staff [member] or student gets harmed by the virus? How will we respond and support that individual and their family? Our staff has lost loved ones to COVID, and not knowing how the virus behaved created an incalculable risk we have been managing since. We re-opened schools knowing that risk has always been there, and that question still remains today.

THE IMPORTANCE OF A HEALTHY CULTURE IN TIMES OF TUMULT

We’ve learned that nothing is permanent and everything has an expiration date. That may sound morbid, but it’s actually freeing. Now that we have been through this, the work of change and adaptation will come much easier.

It’s almost like we were shaken out of a deep sleep and now we can appreciate the work and each other in a much deeper and more meaningful way.

Throughout it all, I’ve learned that climate and culture are still king. There is the old saying that culture eats strategy for breakfast, and it couldn’t be more true. If you are not talking about the culture of your school you are going to have a very challenging time getting the most of your staff and students.

Personally, I have learned that the small stuff is small stuff. Personal connections, partnerships and trust drive everything else. Documents and spreadsheets will always come and go, but keeping the main thing the main thing is something I will absolutely be carrying with me. When staff remember this pivotal year, will they remember how they were treated? Were they heard? Did they feel part of something bigger? What are kids going to remember in this once-in-a-lifetime pandemic? I hope they will remember we were there for them. That we provided a safe, positive and supportive place for them.

As part of the "Leadership Through the Pandemic" series, writer Pamela McClanahan also interviewed Dr. Roli Dwivedi, who is an Assistant Professor of Family Medicine and Community Health, and Chief Clinical Officer at the Community-University Health Care Center at the University of Minnesota. Dr. Dwivedi discusses the challenges of meeting patient needs during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, how her teams embraced a blend of in-person, online and hybrid medical visits, and how they mobilized testing and vaccination efforts in communities with low levels of trust in the medical industry.

While visiting the Northwest Angle, One Greater Minnesota reporter Kaomi Goetz shared a story about the state’s last one-room public school where children in the tiny community – population 125 – learn through a form of mostly independent study until the end of sixth grade. After that, many are homeschooled, while others make a three-hour round-trip journey to Warroad, Minn., where they complete their studies.

If there’s one fairly universal experience triggered by the global pandemic, it’s that we’re all spending a lot more time at home. Many grown-ups navigate virtual workplaces, while kids focus on virtual school. With more to juggle at home, many families rely on intergenerational options that have myriad benefits for both kids and the older adults in their lives. Discover more about this intergenerational connection.