Is It Time To Let Go of the 'Little House on the Prairie'?

Laura Ingalls Wilder's books are filled with rosy depictions of white settlers and racist depictions of Native Americans. It's time, some say, for different stories.

As a child, Linda Sue Park read The Long Winter over and over and over. But she knew where to hold the pages together so she wouldn't have to read the hurtful parts.

"I tried to insert myself in that world in my imagination, because if I could do that, I could somehow figure out this puzzle of how to belong here in the U.S.," said Park, a Korean American author and Newbery medalist.

She could picture herself grinding wheat, twisting hay, helping the Ingalls family survive a brutal winter.

But once she grew up, she realized why the books hurt so much.

Laura Ingalls Wilder's semi-autobiographical Little House on the Prairie series typified our rosy cultural image of the white pioneers who settled in the American west after the Homestead Act.

But it's an image filled with racist and anti-Indigenous stereotypes. When the Ingalls family said horrible things about Indigenous people, Park felt like they were saying horrible things about her.

"Here I was trying so hard to be part of that story, and realizing that I would have been completely rejected by Laura's family," Park said.

Though the first book was published nearly 90 years ago, the series has had staying power.

A new Twin Cities PBS-produced American Masters documentary, Laura Ingalls Wilder: Prairie to Page, premiering Dec. 29 on PBS, looks at the "cultural legacy and complicated history" of Wilder.

"The novels, as she left them, are almost works of folk art that capture the attitudes of the time," Caroline Fraser says in the documentary. Fraser is the Pulitzer-winning author of Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder.

Wilder received an eponymous lifetime achievement award from the American Library Association in 1954. Her books are widely considered classics, often part of school curriculums, and were adapted into a long-running television series in the 1970s and 80s.

But some are rethinking Wilder's legacy. The American Library Association dropped Wilder's name from the award in 2018 due to her depictions of Black and Native Americans, citing "expressions of stereotypical attitudes inconsistent with (the association's) core values."

'That's miseducation'

"We expect teachers to do right by kids. That means giving them facts," said Debbie Reese, a Nambé Pueblo scholar and educator.

"And when they use a book like Little House on the Prairie as if it's an accurate representation of that part of history, that's miseducation."

Reese is founder of American Indians in Children's Literature, which analyzes representations of Native American and Indigenous people. Her website features dozens of entries about the books.

The racist illustrations. The romanticized passages about hunting people. The 1935 edition of Little House on the Prairie, which contains the passage, "There were no people. Only indians lived there." (The word people was changed to "settlers" in later editions.)

She points out the series' frequent use of the phrase "the only good indian is a dead indian" — a phrase she says educators wrongly give a pass because of the books' classic status.

These depictions have a price. They're miseducating non-native kids, Reese said, and putting native kids at risk.

"The cognitive dissonance that a native child experiences when they read that kind of thing in a sanctioned text throws them into this space. ... It's unsettling," she said.

Wilder's books are fiction, but they're often used as education. They're not an accurate representation of the way native people lived in the 1800s. They're not even an accurate representation of the way white settlers lived in the 1800s.

All this is more than enough reason to take the books off of school shelves, she said.

Erasing history?

Other "classics'' have fallen in and out of public favor. Huckleberry Finn and Uncle Tom's Cabin were initially banned after publication for their use of racial slurs, and continue to be challenged.

Today's racial justice movement, reignited by the police killing of George Floyd, is also looking at the role of public monuments and the legacies of some of the figures they honor.

In Minnesota, where some of the Little House series takes place, a Minneapolis lake once named after slave owner John C. Calhoun is now Bde Maka Ska, the Dakota name for the lake.

And in Mendota Heights, the school board recently voted to strip the name Henry Sibley from a high school because of his role in the execution of 38 Dakota men in 1863.

The renaming drew outrage from some, who said the moves were "erasing history."

In a Facebook post, State Rep. Jeremy Munson, R-Lake Crystal, called the renaming of the Mendota Heights high school "presentism," which he said was "judging people of the past by current standards," and without context.

Reese said there's a sense that nobody thinks like Wilder did anymore, that people know better now. But that's not true.

"We look at the president, he says things like she said about people. So that's not an idea of the past. It's still very much an idea of the present," she said.

Similarly, there were many white folks back then who didn't agree with the way Wilder was writing, Reese said. It has always been anti-Indigenous, and shouldn't be considered an artifact of the times.

The danger of the single story

Books are emotional. They contain lots of memories. An indictment of your favorite book can feel like you're throwing your family under the bus.

For Park, who connected so much with the Little House series as a child, she couldn't let go of the books without working through her feelings about them.

"(Putting aside the books) would have been like saying to myself, 'Well, you were a stupid idiot as a kid, weren't you?'" she said.

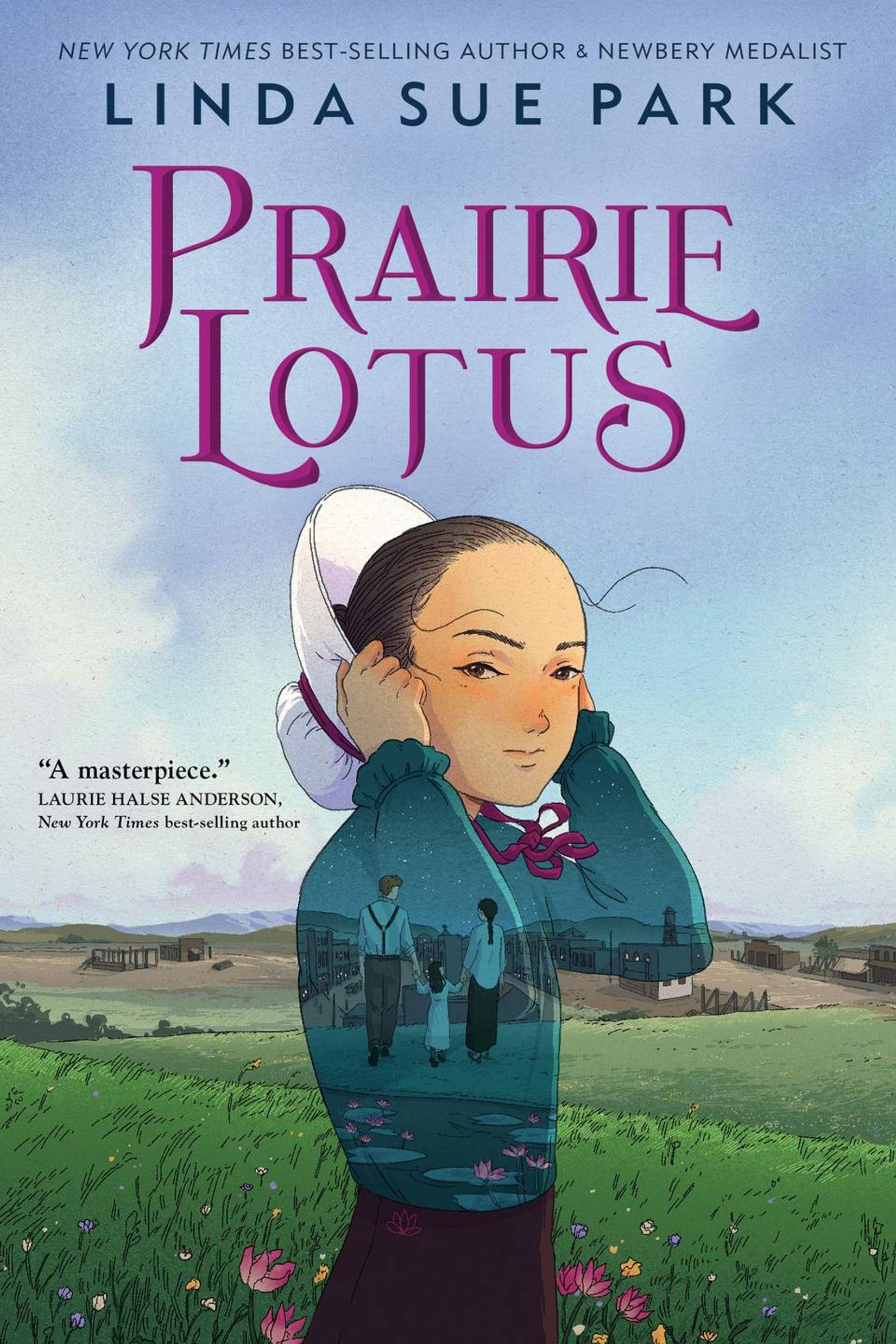

This spring, she published Prairie Lotus, a children's novel that takes place in the pioneer times of the Little House books, in Dakota territory. The book's heroine is an Asian-American girl, Hanna.

Park wanted to preserve things that were good about the Wilder books: the idea that daily lives, including "women's work," could be literature. That you didn't have to do something grand and heroic for it to make the page.

But Prairie Lotus is also a deliberate acknowledgement that it's time to move on from the Little House books.

"I'm not under any delusions that my writing a book in which I do insert myself, or at least an Asian character into this scenario, is going to undo all that history. But it's a place to start," she said.

"It's a place to say there were other people there, there were other voices there. It was not all as heroic as the given single-story would have us believe."

This article was created in partnership with Rewire.

Gretchen Brown is an editor for Rewire. She's into public media, music and really good coffee. Email her at [email protected], or follow her on Twitter @gretch_brown.

When Land O' Lakes decided earlier this year to remove the iconic Native American maiden from its packaging, many celebrated the move. After all, members of the public had called on the company for years to remove what they considered racially stereotypical and culturally appropriated. But Mia, as she is known, was given a refresh by Red Lake Ojibwe artist Patrick DesJarlait in 1954 – and his son, the artist and activist Robert DesJarlait, has mixed feelings about the company's decision. So we wondered: Is Mia a racist trope or a symbol of Native pride?

Believed to be the first person of African descent born in the territory that would become Minnesota, George Bonga was a larger-than-life history maker. Educated in Montreal, Canada, George returned to the Leach Lake area of Minnesota to follow in his father's and grandfather's footsteps as a fur trader. But his life took many twists and turns along the way. Discover more about this Minnesota Black pioneer.