Comedy in Color: A Roundtable with Minnesota-Based BIPOC Comedians

Three jokesters share how they bring themselves - their experiences and POVs - to their art.

The pause between the end of the punchline and the opening chords of a laughing crowd only last for a second, but there’s much more than silence in that pause. Something happens in the audience’s mind. A bond is formed. A connection is made. The performer and the observer become separate components of a singular entity. This is the magic of humor. Though not specifically reserved for comedians - musicians, poets, actors and teachers can all surely relate to those incredible moments - there’s something about laughing, and making someone laugh, that is a wholly unique experience.

There are few experiences more universal than laughter. Humor is as integral to the quality of life as eating, sleeping and breathing. But laughter is more than a collection of reflexive audible contractions. It’s a nonverbal, though decidedly vocal, expression of trust.

The jury is out on the origin of laughing, but many evolutionary psychologists believe that we developed the ability to laugh simply because it brings us closer together. We’ve all heard various sentiments on the healing power of laughter, some anecdotal, some backed by research.

Either way, laughter is a powerful force in the human experience. And those who possess the gift of eliciting laughter are more than just talented: They’re wayfarers. They're able to bring a distinctive voice, and with it, their views and experiences, to the masses.

By sharing themselves and being funny, they expand more than the diaphragms of their audiences, but also their overall worldview as well. And an expanding worldview sparks compassion and empathy, two of the most effective vaccines against many societal ills - racism in particular. In order for racism to thrive, there must be a dehumanizing effect. The bigot must distance, or “other” those who don’t share their physical characteristics and/or ethnic heritage. Seeing people as something other than people allows prejudice and ignorance to fester. But the realization of commonality can trump hate.

When you think of Minnesota comedy, a few names immediately come to mind: Al Franken, Louie Anderson, Maria Bamford, Mo Collins, the late, great Mitch Hedberg. Your parents may have listened to A Prairie Home Companion. Your grandparents may have laughed at the antics of Pinky Lee. While all of these luminaries were undeniably great, it does paint a fairly monochromatic picture of our homegrown humor.

But the truth is that our comedy is as varied and diverse as a spring forecast in Saint Paul.

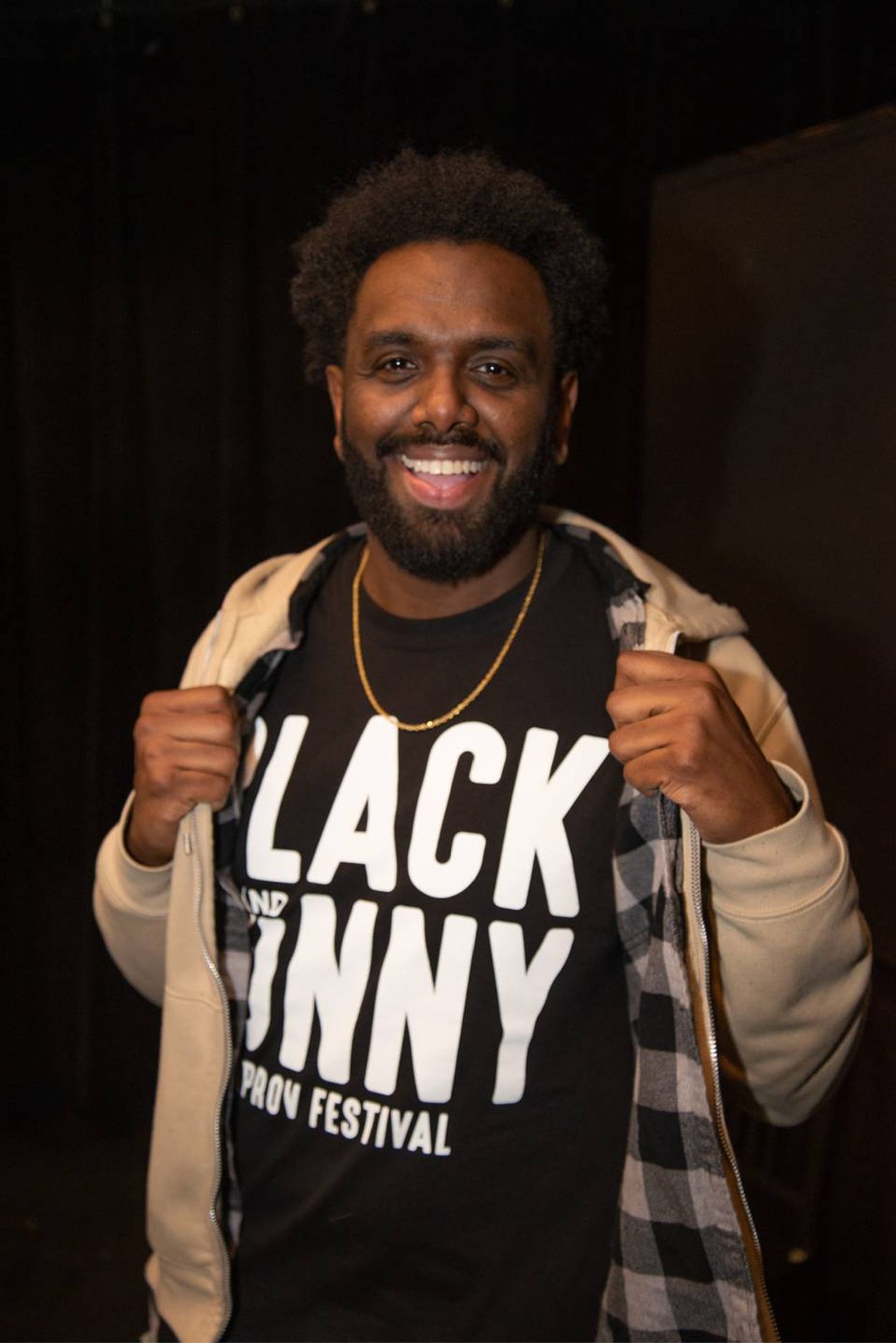

John Gebretatose and Joy Dolo are founders of Blackout! Improv Comedy, a Minneapolis-based improv comedy group. Performances cover the standard improv games and audience suggestions, but also feature segments, where special focus is given to civil rights issues like police brutality, white privilege and cultural appropriation. Miss Shannan Paul is a standup comedian, speaker, radio host on MyTalk1071, co-host of the BeOurGeek podcast and a regular on The Jason Show on Fox9. I sat down with these three incredibly talented - and hilarious - Twin Cities performers to gain more insights into how they break a leg, while breaking new ground.

So I know this is a question that performers get all the time, but what brought you into the art form? Why comedy? Was it sort of a fluke, like you had a few friends that said you were funny and pushed you on stage, or you got older and realized you were funny so decided to try it?

JOY DOLO: Well, I got into performing when I was in sixth grade. Because I was also very nervous and shy. I grew up in Fridley and I’m first generation Liberian. So I didn’t fit in with like African people, because I sound like this. But I didn’t fit in with Black people…because I sound like this, and I didn’t fit in with the white people because I look like this. It was just a whole cacophony of….nonsense. So I was very alone, very shy, didn’t say much, and Kevin Duncher came to my lunch table and said, “Hey, do you want to be in a play?” And I said, “No.” And he said, “Okay, I’ll see you at auditions after school.” So I auditioned for Snowy Off-White and The Eight Little Dudes. I created the role of Itchy. And I had three or four lines, and they were all very funny. There was something that happened when I said a line, and people reacted, so I think that was my first seed of confidence. So as opposed to going a different route growing up, I only went through theater.

JOHN GEBRETATOSE: Well, I’ve been funny since like, kindergarten. We had a Santa Claus that came in, and there’s nothing weird or wrong about it, but he was Asian. And I was a young kid, and I said, “Well, the Santa that I know is white, not Asian,” so I pulled his beard down - and this isn’t anti-Asian - but I had everyone laughing, including Santa. Even he thought I was charming because of how I went about it.

JD: And then he went home and drank a whole fifth of vodka?

SHANNAN PAUL: Was that his last day? Oh, John.

JG: Ha! No, I mean. Y’all stop. It was like, it just demonstrated that I was down to do like, whatever to make other folks laugh, and if we get in trouble for that, it just means I have to pay the price. But I didn’t know I was funny professionally until I worked in advertising and had to go and pitch and talk to all these mostly white clients. But I wasn’t big on public speaking and still had to talk to these folks about why they should like my ideas. So I went to comedy clubs just to work on my public speaking. I was at Grumpy’s, it was just one of those places you could just go up and work, and then after a while, I thought, well, I’m just going to keep doing this because advertising is whack.

SP: I was a nerdy kid, and humor was a good way to get people to not pound on you because you were nerdy. And I had self-esteem issues, to the point that other people were more supportive of what I was doing than even what I saw. And just because of my particular family dynamic, it was you’re not supposed to be prideful or show off or you don’t have to be the lead. And it wasn’t until a few years went by that I though, well wait, here’s a laundry list of all the things that I’ve accomplished, not only should I be proud of me, but my family should be proud of me. Instead, they were like, "Why you got to be so…uppity." And I was like, "Look, I have earned uppity. Okay." And actually I thought I was going to be an attorney. Because I liked speaking, I wanted to be an orator, you know. I watched too much Perry Mason and L.A. Law and...

JG: ...it turned out to be like Night Court?

SP: And not even that! I didn’t even get to talk. I ended up working for a few law firms, but it was a lot of writing letters and boring stuff, and back-room wheeling and dealing, and I thought, well, I don’t want to do any of this, so I ended up switching my major to marketing. And I was still in a bunch of writing classes and thought eventually I would do that as a side gig. A friend of mine, Michael Libby, we used to go to Acme all the time, and we just hand. They used to do 2-4-1 passes, and we’d go drink and check out the open mic. And we’re there one night, and he said what other folks had said, like, "You’re funny, you should do this and that." I responded "No, I just tell stories and stuff to my friends." And he said, “Well, what do you think they’re doing? You just have to make your stories jokes.” And it just clicked that time. Even though people had said I was funny before, it just, like, sunk in. Like, oh yeah, I can make that a joke. I was going to Metro State at the time, and I was in a comedy writing class and instead of writing a one-act or a short story like I would’ve done, I wrote a comedy set. I had to write four minutes and I told it in class and….I didn’t die. Then I tweaked it, got it down to three minutes, then went over to Acme, and - well, here’s the thing - when I get nervous, I sweat, so I’m sweating, but people didn’t notice. So, I seemed okay to them. And that was like, jeez, 20 years ago now.

JD: I started doing improv with Theater of Public Policy, and my first improv experience was actually doing an improv show. I didn't have any training. They're just like, "Oh, you're friendly." So, I did the show with them. And they're like, "That was really great. Let me ask you to be in the troupe like that after graduation." And then I was like, "Oh, there's a bunch of white folks everywhere I go, how do we fix that?" And then we got into Blackout.

But it's not just like, you know, doing the improv or doing the performances, it's all the sh*t that goes along with, right, like, it's a lot of work - you got to be organized, you have to be really be communicative. You have to know how to save because it's either feast or famine, right? Sometimes there isn't work…COVID! You have to know how to really handle your money, handle your business and handle yourself.

SP: And you’ve got to figure out how to pivot. I mean, because part of the reason I've been working is to learn how to work in this new world. And what am I going to do and come up with a new project, some of my friends that just couldn't do it. It's not fun to them. It's not the way they were fueled. But I'm like, “Oh, no, no, I got bills.” And it was also, if I can figure out how to keep working during this time, when things come back, I'll be able to do that, too. So, how can I make sure that I’ve either maintained or grown my following so that I'm one of the first people that gets to go back to work when shows come back. And I think that not only is it difficult for performers, I think it's extra difficult for performers of color, because you're layering and traumas and things you have to deal with on top of everything else. So to be like, "I'm going to go and kick this door down and figure out how to show up and present this, and pitch this, and do that," you just have all these layers on top of it. It's emotionally draining sometimes to do all that stuff, especially if you're performing in the Midwest. I mean, it was bad enough when I was in Arizona, but it's sort of a different racism in Arizona. Here it's a lot of, you have to have the right mindset. If I'm showing up and doing a show in some sixth-ring suburb, it's like I have to know how I’m going to present myself. Like, my name is on the poster. I'm supposed to be here. You have to walk in and basically figure out a way to create dominance.

JD: Like shoot a gun in the air, "Are y’all ready to laugh!”

SP: That’s right! I walk in with all the presence, "Yes, she came to perform."

JG: So, this is an analogy I like. When you get your driver's license, that's one thing, but they never teach you how to drive in the winter. Being a performer of color? It's like having bald tires. It just feels like, sure, anybody can do it. But man, you’ve got to adapt and pivot and you’ve got to really want it, too. There's a lot of people that are really talented, and God bless them if they're just like, I don't know, man, I just thought the world come to me, right? And good for them if that happens, but like…networking, like, you should probably know how to do that.

JD: I think networking is important, but there also is the thing of being a person that is marginalized and trying to get into an industry that only sees a certain type of person. Like when you do improv comedy, what's the joke? It's always a white guy with a beard and flannel shirt. And that's what it is nationally, all over the world. That's what comedy is to most people. So walking in as a Black woman, or any other kind of identification, you have to know people are going to have an idea of what you are, before you say what you're going to do.

You're all unique and distinctive in what you do. What are some things that have been pretty much consistent throughout all the work? What are some things that you thought would be better now, as far as crowd reactions, attitudes, treatment from booking agents? Because you're still sort of unicorns, right? When you think comedy in Minnesota, you think Louie Anderson, Maria Bamford, you think of Mitch Hedberg. Are you still met with expectations to fit into a sort of L.L. Bean catalog in Connecticut kind of vibe?

JG: One really good thing right now, is we have a solidarity with the folks of color in this community, the marginalized folks. We have an understanding, and I really love that. I didn't think I'd see that in my lifetime. But it felt natural because like, I’d see Shannan, and Shannan was good to me. And then I was seeing other Black comedians, and they were good to me, and it’s just great. It’s easier for people to just get in and have a community and care. Like when women started speaking up and calling out sexual abuses and all that, I felt like it really snowballed in our favor, meaning we can take shows, and if bookers or clubs are weird about it? Then hey, we're going to do what we do anyway, so take it or leave it.

And that poignant aspect, was that always part of it? Because like, the stuff that you do, Shannan, with your radio show and podcast, the stuff Joy and John do with Blackout, it's not just funny. There's that layer of poignancy. Like you said, John, you get real. It's a natural fit. But when and where did that come from?

SP: Like you're supposed to when you're a comedian, you're supposed to come up and deliver punch lines and hit it. And that's all fine. But I choose to not do that. I remember being out on the road and going and I had a great set, and it didn't feel right. It didn't feel fulfilling, there was something about it, and I needed to figure out a way to make my art make the lives of other people better....I know I can Mae West if I need to. I can always throw swear words into a joke. I could come up with a poop joke if I needed to have one. I just don't.

It is so great to have performers like Joy and John and everybody else that's out here now, because what we've done a good job of in this community here lately is to get rid of that, you know, I've talked about the Highlander mentality before, because it was pitting ourselves against one another. Because if there was a show, there could only be one Black person. And if I showed up, then there might not even be another woman on it. Because they're like, we got a two-fer. So it was competition. Trying to make us not want to work with each other, right? Like we know we're completely different people, so not letting that narrative continue to be told that if you have two Black women on the show, we're gonna have the same act. So I just started booking shows that were all female and not promoting them as a women's show. If I had a show that happened to have a lot of BIPOC performers, I didn't put a name on it because then you would get this pushback from the Caucasian performance community. Because if you say that there's an all-Black show, then they get mad. And it's like, well, you inherently have had all these wild "white shows."

JD: It’s interesting because I feel like when you start thinking about being funny in comedy as an art, as opposed to just being on stage, there's something precious to me about it, something precious about the way we go about it, the way we put together a show, the way of communicating with the audience afterwards. I take it very seriously, and if you take something seriously, it's going to give you more agency. I'm not going to let anyone in the audience, anyone in any institution, tell me what I'm going to do with what I believe is right. And I feel like Minnesota is bad at a lot of things, but one of the things that I like about Minnesota is that we have a lot of arts opportunities - for grants and things like that. And you can have a lot of agency in what you want to create. Your earlier question was what’s something that could change? In the theater world after George Floyd was murdered, there were a lot of institutions coming out saying their racial policies and it's like…it's 2020. Even after you had that one Black show two years ago, why are you coming out with this right now? So for me, and people that I've talked to, there's a sour taste in that the community right now.

SP: Yes! I've had some offers and gigs, and it’s like, "Okay, where are we going with this?" and also we want to have a committee? Well, what are you going to do with this? Am I going to spend a lot of time creating a document that's just going to go on the back page of your website so you could say that it's there, but it's actually nobody on your board really reads it or cares?

One of the things I really like about Blackout, is that you do bits - like a lot of improv groups do - but you'll have the parts where you sit and you start talking, and it's not just talking about the premise, it's actually talking about why this premise works, why is this important. And I don't recall the bit, but in the conversation part, between you and I think it was Denzel, you were discussing the use of the N-word by Black people. And that's usually not something somebody thinks about or expects when they're going out to see an improv show.

JD: One of the great things about Blackout is that we are able to showcase that Black people are not a monolith. We all think very differently. We all are a product of our environments. It is totally fine that Denzel, or whoever, doesn't say the N-word. And it's totally fine that John wants to say it, because we our own individuals with our own paths and our own thoughts. Going back to this thing of trying to pit people against each other, we are showcasing that it is possible to have a conversation with someone and disagree and still be funny.

SP: I think that theaters do have the ability to be a community hub and to be able to give to amplify stories. Because, I mean, there's a variety of different things that we're all good at.

And with the pandemic (hopefully) easing back, or at least getting under control, what’s up next for you all?

SP: There's a gig in Fargo, and I'm headlining a show there. Because I haven't done any out of town gigs since things shut down. Did you know they have one of the top 10 bagels in the country at a place in Fargo? Yes, they do. So do I have something to look for? Yes, exactly. But I'm excited to do this show. And I just have one that I just started doing, a Sunday night livestream with my best friend. It's called The Black Unicorn, the White Witch. We talk pop culture and just stuff that is out there and interesting stories. And we do it on Facebook and YouTube just to continue to build our audience and to talk about things that we like and just to build a community and go, hey, there's this place that will do for half an hour, 45 minutes, and everybody's just kind of checks in, you know, throws some comments in the chat. Know sthat we're just here and there.

JD: I mean, we've been working through the pandemic as well doing the panels. So we're going to continue doing that. And in 2019, we traveled a lot of different places internationally. So, I'm excited to get more into the international comedy scene, which is really exciting.

JG: And the Black and Funny Improv Festival, that’s in June. Kind of a hybrid, indoor-outdoor thing, at the Bakken Museum. And I feel like we're in our groove. Blackout will have been going for six years in September. And that's like, we have our thing and we're really like excited to show you what’s next. Because, we've been funny, we've been on it, and now it's like, everybody's been through a crisis. So, let's all be comfortable, and…laugh.

Photography by Angela Doheny

T. Aaron Cisco is a cultural essayist and author. His latest book, Rod String Nail Cloth: An Afrofuturist Mixtape reached the top five on both Amazon’s Top Science Fiction Anthologies list and Amazon’s Black & African American Science Fiction Top 100 list.

Writer T. Aaron Cisco also interviewed Vincent Hopwood, a Black Minnesota-based motorcycle rider who fits precisely zero of the stereotypes anyone has about what bikers should look like. Burly, bearded dude on a growling Harley-Davidson? Nope. Sport biker in form-fitting gear who thinks the world is his track? Not at all. Find out how this Black motorcycle rider is "more than a unicorn."

Teamed up with fellow comedians Elise Cole and Khadijah Cooper, Ali Sultan founded the outfit People of Comedy with a singular aim: to expose Minnesota audiences to comedy that reflects a richer range of perspectives and experiences that what’s often showcased in the mainstream scene.

“Mementos of civil unrest pepper the walls of buildings and storefronts. Plywood boards still cover broken windows of some shops. Signs reading “George Floyd” and “Black Lives Matter” are spray-painted across Lake Street. A database at the University of St. Thomas has catalogued more than 1,300 similar graffiti and murals in each U.S. state and 76 countries. There are fewer protests, but more tense moments like that traffic stop.” Data Reporter Kyeland Jackson offers this dispatch on the aftermath of George Floyd’s police killing in May 2020.