Pennies On The Dollar: The Beginning of the End for Estate Recovery?

A proposed bill could give all states the chance to end their estate recovery programs.

A new bill introduced to the U.S. Congress could end estate recovery programs across the nation.

The Stop Unfair Medicaid Recoveries Act of 2022 would stop liens from estate recovery, a federal program that requires states to claw back Medicaid expenses by going after the property and homes of dead recipients. The bill would also prevent recovery from the deceased, and give states the chance to end their recovery programs. Advocates say that this may be an unprecedented step towards ending estate recovery across the nation, and it's gathering support. More than a dozen legislators, including U.S. Representative Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.), have signed onto the bill, and Minnesota State Senator Jason Rarick (R-Pine City) said that federal talks to end estate recovery could gain traction in the North Star State. But this isn't the first time that state legislators have debated changing the program. The most recent effort to do that started more than an hour away from the Twin Cities in a town of less than 400 people.

The Beginning of the End?

It began with a conversation in Willow River, Minn.

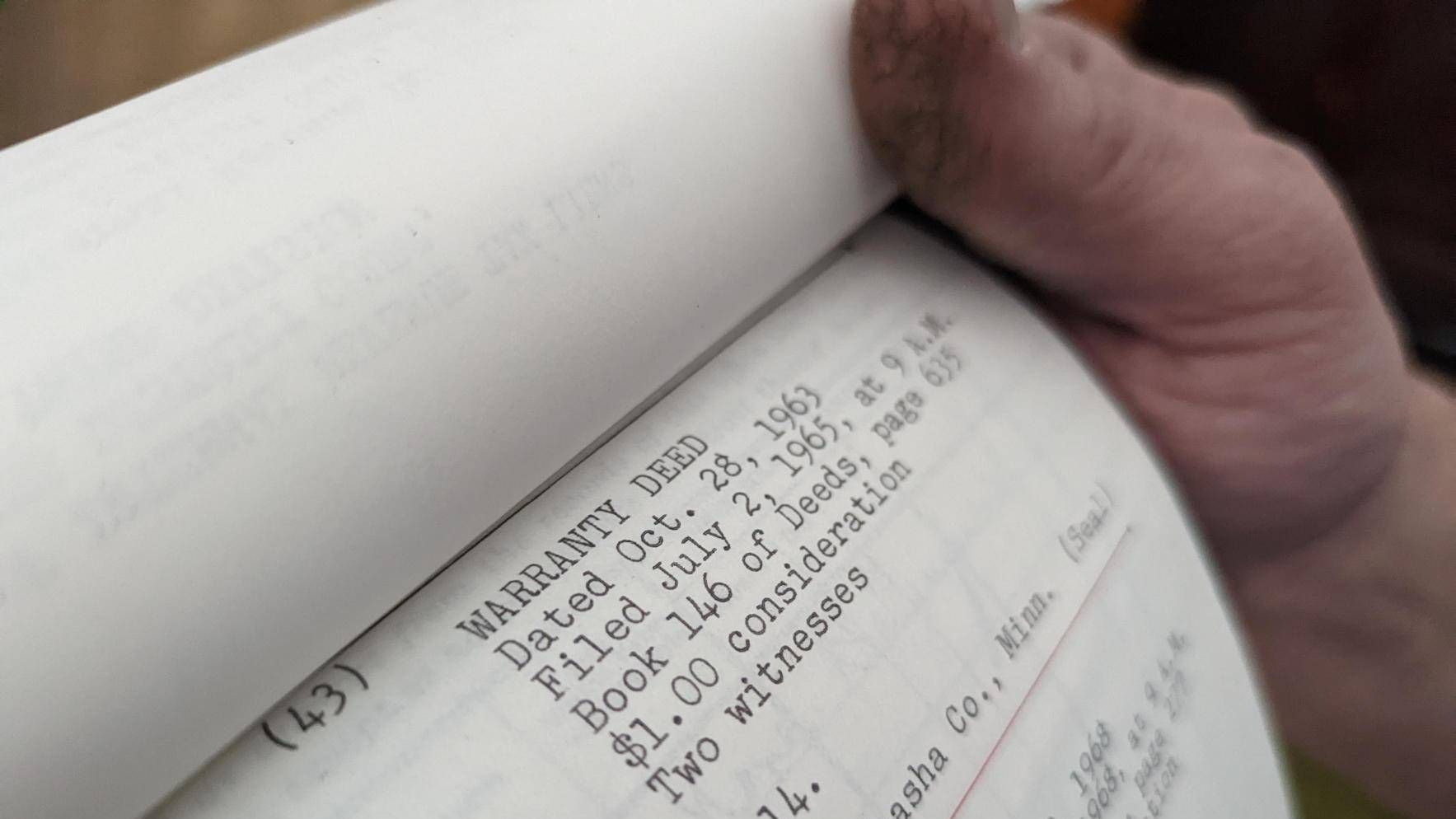

Rick Rayburn, a retired Minnesotan who had signed onto the Affordable Care Act in 2013, heard from his neighbor that a clause in their insurance application mentioned liens and recovered property. That's how Rayburn discovered that coverage for low-cost insurance in Minnesota would be clawed back through estate recovery claims on their homes and wealth. The more that Rayburn researched, the more people he found who felt blindsided by estate recovery claims made because of their Medical Assistance coverage. Many of those people are single women fighting to keep their family's legacy.

"One woman, they had a lake cabin her father owned. He was a World War II vet. For seven years, they kept bringing her to court to get that lake cabin," Rayburn said. The state eventually won that case, and her father's cabin. "There's a lot of ways [estate recovery] can be done very compassionately with minimum recoveries … Minnesota has one of the harshest recovery policies of any state."

Grassroots organizing, media attention and lobbying pushed Sen. Rarick and other legislators to pass a 2016 law limiting the number of estates Minnesota's recovery program could take from. The Stop Unfair Medicaid Recoveries Act could do the same thing on a national scale, and Eric Carlson said it could be unprecedented. For more than 20 years, Carlson has served as directing attorney for the nonprofit Justice In Aging organization. Officials referenced his work in a 52-page brief to Congress that recommended changes to estate recovery. He's optimistic that the bill will progress towards being passed, but he also worries that stalling this would keep families in poverty.

"This is the only public benefits program that collects from the estates of deceased beneficiaries," Carlson said. "If people are broke, essentially, and eligible for Medicaid, it's appropriate that the state provide for health care so those folks have the long-term care that they need."

Efforts by Justice in Aging and other organizations have lifted California as a model state for recovery reform. If Minnesota wants to address estate recovery, Rayburn says that people should follow the Golden State.

The California Model

Most of the estate recovery hearings that Pattricia McGinnis has attended were against people who were low-income, in intergenerational families, or were of color. If you ask her, the program has been horrendous for residents.

McGinnis is the director of California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform, a nonprofit working to improve long-term care for state residents. Her organization helped to lead reform for estate recovery, making recommendations to the nonpartisan Medicaid and Chip Payment and Access Commission. McGinnis said that California's estate recovery program used to go beyond federal requirements, billing residents for extra property and services. After years spent pushing for legislative change, California passed a 2017 law that restricted estate recovery back to what was federally required – such as long-term care services and prescription drugs. She says there were around 7,000 estate recovery claims in California when the law started. By last year, that number had shrunk to under 300.

"I think the governor understood how unfair it was and how unfairly applied it was. And secondly, that during a period when they were trying to get people registered for Affordable Care Act benefits, people were not doing it. They were reluctant, and I don't blame them," said McGinnis, explaining that estate recovery discouraged some people from getting health insurance. "It's not just about inheritances. The people in the cases that I've had, many, many, many of them, are intergenerational families. Farm workers. People who've worked all their lives [and] paid taxes."

It took a handful of rejected bills for California to curb its estate recovery program. But McGinnis is confident that the Stop Unfair Medicaid Recoveries Act will make a difference for other states. The bill's sponsor, U.S. Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-Ill.), would agree.

Schakowsky first heard of estate recovery in 2019. Since then, she said many people have shared stories with her about selling their family homes to afford recovery. She hopes to gather more support from legislators and residents in order to bring estate recovery programs to an end.

"It doesn't bring very much money to the treasury, it doesn't really help in any way to reduce the deficit – it's so small. So there's no reason to continue this burden," Schakowsky said. "The fact that activists and families and ordinary people have gotten involved is absolutely critical. We need to keep that up, and we need to expand it. But now that there's actually a piece of legislation to back them up, I think that we have a much better chance."

It's unclear how much support ordinary people have put behind Schakowsky's bill. But many Minnesotans, like Kevin White, are still struggling with the consequences of estate recovery.

Is The Trust Lost?

Since Twin Cities' PBS first posted White's story, dozens of people from across Minnesota have contacted us. A few have shared good experiences with estate recovery, thanking the program and taxpayers for the care they bought their loved ones. Most have shared stories about negative encounters, recalling family farms that were lost, intergenerational homes that were threatened and moments where people feel they were unheard.

Despite the sacrifices he's made paying to fight the state for his house, White plans to continue so that his son can experience what he grew up with. His advice to others: "Try to fight for what you believe in."

Editor's note: An earlier version of this story said the Stop Unfair Medicaid Recoveries Act of 2022 would limit liens. The bill would, in fact, stop pre-death liens and post-death estate recovery.

Kyeland Jackson's reporting on estate recovery was undertaken as a USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2021 Data Fellowship Grantee.