Black Churches Heal Many Wounds in a Turbulent Year

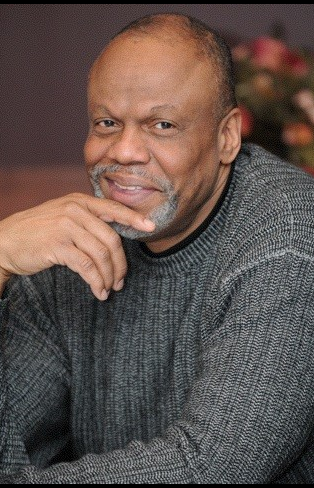

Rev. Alfred Babington Johnson is a community leader, convener and CEO of the Stairstep Foundation who has an ear bent to Black church leaders across the state. So he sees firsthand how congregations are living and dying during the pandemic - and he knows African Americans are less likely than their white neighbors to have health insurance or a primary-care physician. With such a direct line to both congregants and church leaders in all corners of Minnesota, he not only understands, but witnesses, the ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionally affected the Black community. From his perspective, the Black church plays an equally vital role in improving the health of the community as it does in spiritual matters.

Passionate about the role that Black churches play in congregants' physical and spiritual health, Babington Johnson helped spearhead Discovered Truth, a 2019 Twin Cities PBS documentary that examines the history of how Black churches have provided for their communities from within and how the Affordable Care Act carved a path that allowed more African Americans to gain access to potentially life-saving health care.

CAN BLACK CHURCHES HELP?

In terms of their relationship with the medical industry, a troubling history has created a legacy of mistrust between Black Americans and U.S. medicine. Between the Tuskegee Study, which allowed Black men to die from syphilis, and the case of Henrietta Lacks, whose cancer cells were used by researchers and drug companies for years without her consent, it's no wonder that Black communities mistrust physicians and medical institutions. That turbulent history is also why many Black men and women are skeptical of the government's push to vaccinate against COVID-19.

A pastor has a trusted voice. Can the right messenger ease fears and improve trust in order to help stem the spread of the virus? Aside from the medical issues associated with the pandemic, many people are hurting. They have lost their jobs, they grapple with loneliness, and they feel scared.

Religious services - and the community within - provide care and support during trying times. If you lose a job, a church community will step up and provide. If a family member dies a church community is there for you. A topsy-turvy world can be righted, if just for an hour, by worshiping together.

BLACK CHURCHES PICK UP THE SLACK AND ADAPT

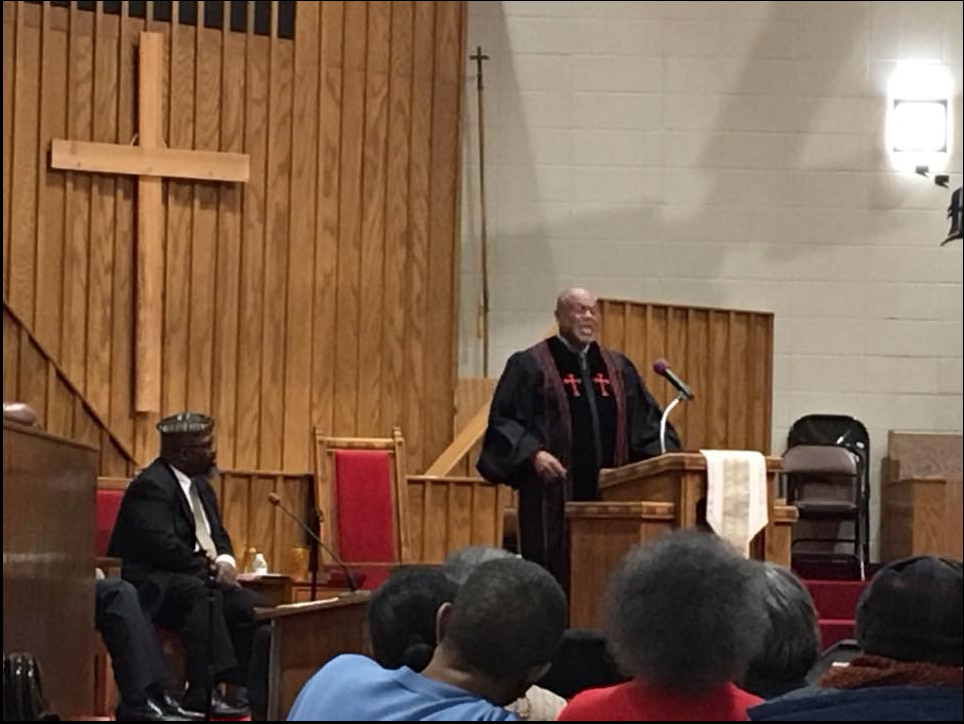

This 2019 documentary Discovered Truth explores the mutual-aid societies created within Black churches.

While it may take years to unpack the long-term impact of all that 2020 threw at Black communities, Black Americans have born the brunt of health and wellness issues sparked by a global pandemic, police violence and systemic racism within the healthcare industry. So we reached out to Rev. Babington Johnson to learn a bit more about how the Black church has provided shelter within so many storms.

How is the Black church able provide support since the pandemic has made gathering in-person groups impossible?

Babington Johnson: It's always a wonderful thing to be able to be in close human contact, but more important is the intentionality and the sense of connection. This causes you to look for new tools to implement these connections. We are using Zoom, computers and social media at levels that will continue to change the ways we relate to one another.

The core issue is about the intentionality. If my brother is on the West Coast and facing a medical crisis, I will call him much more often now than I would under normal circumstances, and he is going to feel my concern because my concern is genuine. It is really about the commitment to connection, which nothing can stop. We yearn for the time when the hug can replace the virtual contact, but we recognize intentional connection is a vital part of healing.

The important [question] is: Are we committed to one another? Do I want to find out how you're doing? Am I going to be intentional about the outreach? The church is doing that, and we have found ways to collaborate with the state in that regard.

How have Black churches in the community been a part of the action plan set by the state?

Our church network, His Works United, made an agreement with the Department of Health in March 2020. Since then, we have created what we call, Community Beacons, made up of over 40 Pastors from across the state. The Beacons create Care Trees to intentionally reach out to their congregations and into their communities to get and provide accurate information about the coronavirus. We can then encourage the kinds of behaviors that can minimize the coronavirus impact. Beyond these behaviors like washing hands and social distancing, we can intentionally raise the profile of the churches into the very heart of the situation.

The churches have been a part of the solution by conducting dozens of testing events and through working with the State of Minnesota. We worked with Fairview M Health and Black Nurses Rock and, again, with the State, churches identified a location within the community where we can test. We had church members involved. The Black Nurses Rock did the testing, and the State of Minnesota did the registration. It was a team effort.

It is important for the church to be involved, not just in a public relations way, but in as tangible a way as possible because it is important to keep the church's trusted voice at the center of the conversation.

Why is it important to have the trusted voice of Black churches help deliver the message?

There's a lot of skepticism in the African-American community around institutional medicine and around government. In critical times such as these, it is important to intentionally engage as a church community, and it is important for the state and federal government to recognize the importance of this collaboration - to support it, resource it and trumpet it.

The messenger matters in this case?

Absolutely. You have to realize that the way you do things is as important as the thing you are doing.

Being fully aware of the history and skepticism that lives in the Black community, how are the vaccines being talked about?

With all of the historical issues, it is important for the community to take a look at these vaccines. It is important for the government to be at the table early on and not just asking us to get the people to come in. We have continued to press the Governor and his staff to have our community involved in the design of the outreach and implementation, just as we were involved in the testing. We continue to be assertive with the Governor and others that we need to be a part of this dialogue and communicate to our folks the efficacy or the danger around the vaccine.

Through partnerships with Black nurses and with African-American doctors in Minnesota, we are working together to help our community understand. We help them understand the dangers and the appropriate kinds of strategies with testimony from our own community. We are a part of the message, we are not not just taking whatever comes over the wire.

We are making statements. We have had several of our pastors and doctors who have taken the vaccine in public because the danger of COVID is greater than the recognizable dangers associated with the vaccine.

We have a real commitment to bringing the accurate information to our community.

Will the relationships formed with the likes of Black Nurses Rock and the African-American doctors last longer than the pandemic?

The primary goal is community building. Crises come. There will be a new crisis at some point - they will always be before us. The idea of building a robust community that believes in one another and is accountable to one another and has a willingness to show up for one another - that's the real prize that we continue to seek.

Even if COVID-19 didn't trigger a global pandemic, 2020 would have been a trying time for all churches, perhaps especially for Black churches. Has the inability to gather presented new opportunities for churches to provide care and wellness for their congregants?

We have had to develop new approaches and learn things that our children and grandchildren know. We have had to work with the technology. This is okay because, at the core of it, the question is: What are our motivations? If you have to find new approaches, you will. In the midst of this, we need to connect and we will find a way to connect.

How do churches reach out to the family that has never crossed the threshold into a church, but is hurting, mourning or facing unemployment?

With the Black church, there are a lot of people going to the church for the services, but who don't necessarily go to the church for the service. This has always been the case. The fact that there are people who are hungry is a dilemma. The fact that there are people who have lost jobs is a dilemma. There are people who are in relationship disarray - this, too, is a dilemma. These dilemmas are a part of life that gets exacerbated in these times of crisis. From that comes both the challenge and the opportunity.

Because of our relationship with the Department of Health, [church leaders] have been able to field calls from people all of the time who are in crisis. Whether it is about their mortgages, or about how to find testing sites, or whatever it may be. This crisis is allowing a higher profile of service into the community.

So many of our African-American churches are stepping up, doing food distribution and delivering food to the elderly, that I feel, coming out of this, there will be a great sense of communion and collaboration with our community around all kinds of issues like education, health and political power.

We are going to use the experiences of this very difficult season to advance the cause of community.

This story is part of the digital storytelling project Racism Unveiled, which is funded by a grant from the Otto Bremer Trust.

"I know that nothing changes unless people change it. And the people who usually have to make it happen are those who are most at risk from the system. It’s a conundrum I haven’t worked out in my mind or heart. No Black parent has. And yet, here we are." Writer Shannon Gibney contemplates what defunding the police means to her as a Black mother and to the future she envisions for her son.

Rates of inequity in Minnesota fall below national standards and show how historical divides have created ongoing consequences for people with darker skin. Some disparities are driven by historical and racist practices like redlining. Others are escalated by the wealth and success of white residents. Data Reporter Kyeland Jackson takes a close look at how Minnesota compares to the rest of the nation when it comes to racial disparities.

Along with other urban centers across the country, the Twin Cities have a history of racially discriminatory housing covenants that prevented people of color from buying homes in certain neighborhoods. That history ripples in the present-day affordable housing crisis: By limiting opportunities for home ownership, people of color were stripped of one key way to build equity over time. Discover more in “Mapping the Roots of Housing Disparities in Minneapolis.”