'Armed With Language,' World War II Nisei Soldiers Have So Much to Teach

The documentary "Armed With Language" draws connections between World War II racism against Asian Americans and present-day anti-Asian hate crimes.

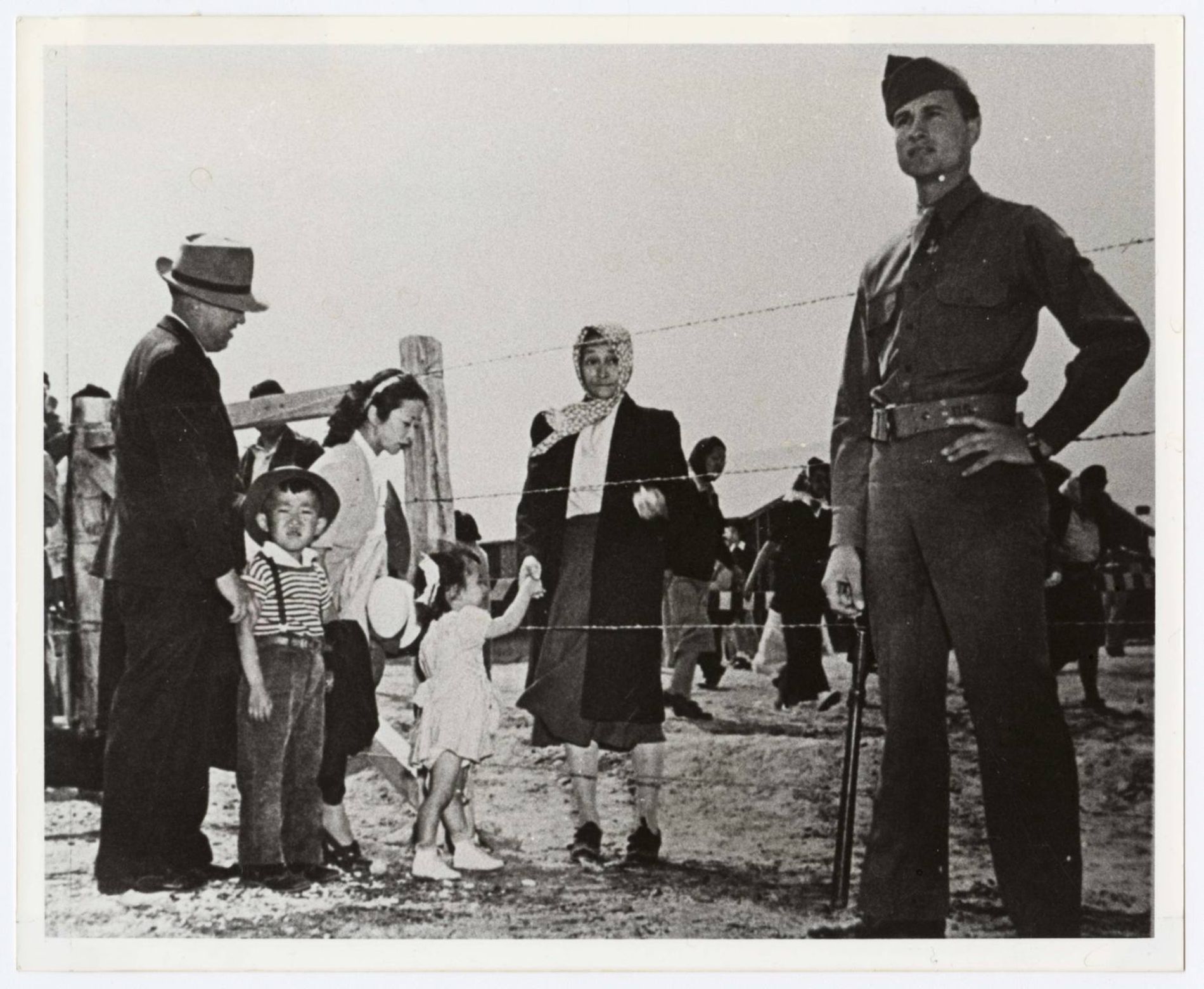

I am a Sansei, a third-generation Japanese American. My first generation - Issei -grandfathers came to this country around 1905. Both my parents’ families were imprisoned in internment camps by the US government during World War II. My parents, second generation Nisei, were 11 and 15 and natural-born citizens. But they and nearly 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent were incarcerated in desolate areas of the West and Southwest in 10 camps, each ringed by barbed wire fences and rifle towers with machine guns. And yet, no Japanese American was ever convicted of espionage.

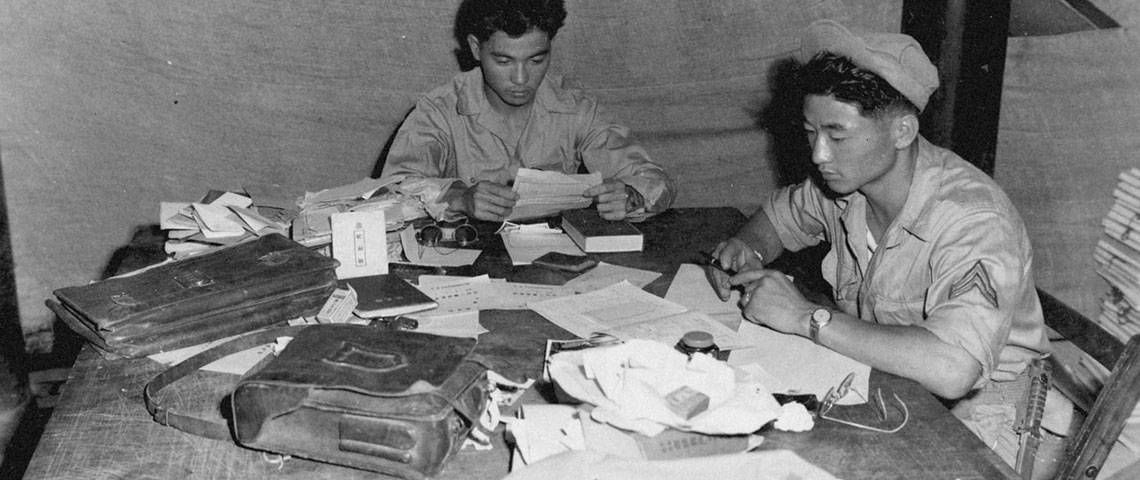

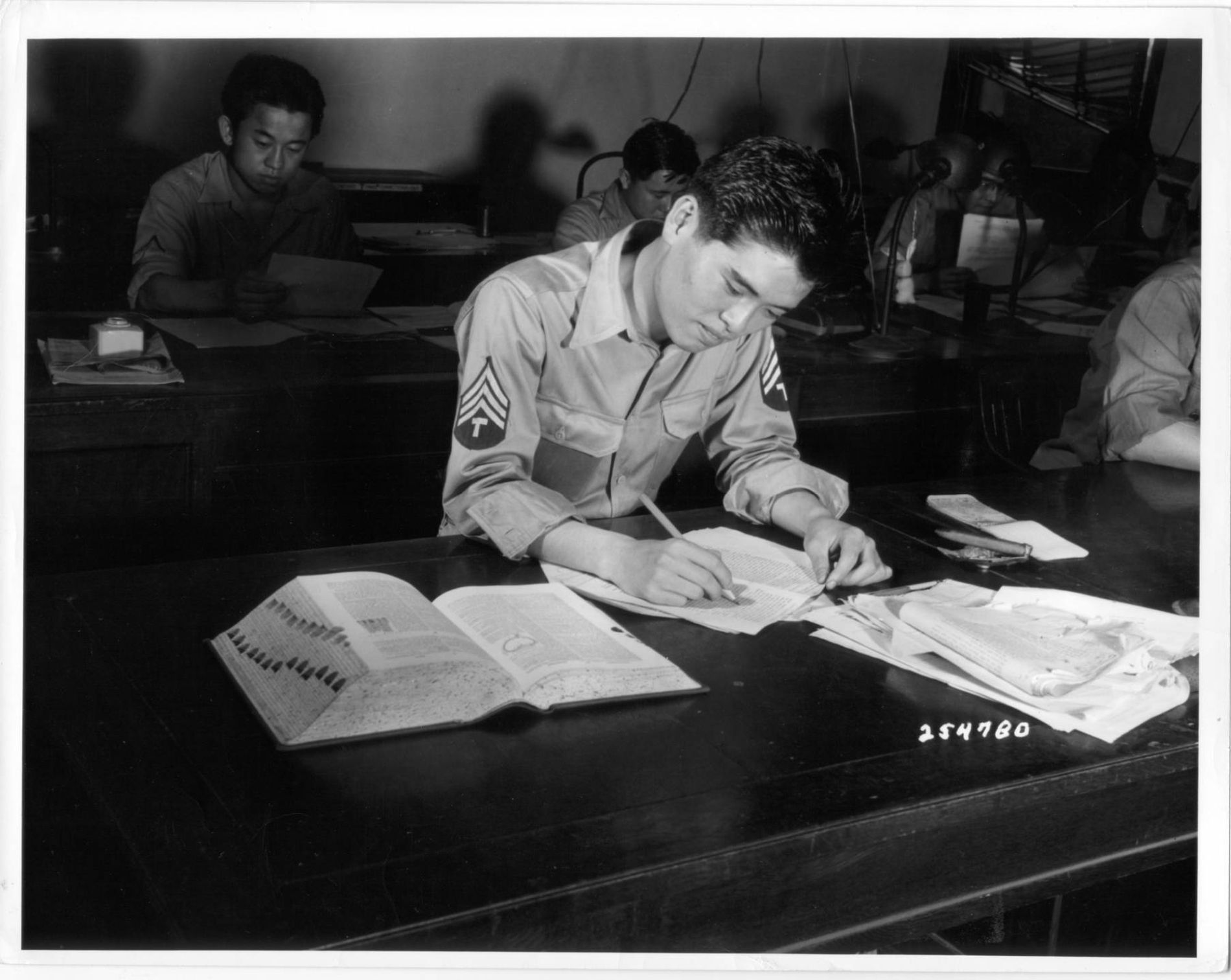

One irony of the camps is that a significant number of Nisei men served in the armed forces during the war. Fourteen-thousand fought in the famed 442nd regiment, which became the most decorated unit in Europe and engaged in some of the bloodiest, fiercest battles of the war. Just as significantly, thousands of Nisei soldiers served as Military Intelligence Service (MIS) linguists throughout the Pacific theater. They translated captured documents and messages, interrogated prisoners, helped US troops maneuver on battlefields, enabled the surrender of Japanese troops and provided absolutely crucial information to commanders forming battlefield strategies. General Charles Willoughby, MacArthur’s chief of intelligence, maintained that the MIS Nisei linguists shortened the war in the Pacific by two years and saved a million American lives. The very cultural background which made the Nisei so suspicious to their fellow Americans, became one of the US military’s greatest assets during the war.

The story of the MIS Nisei and their enormous contributions is still not widely known. During the war, they were trained at a language school at Camp Savage and Fort Snelling. In part because of this Minnesota connection, Twin Cities PBS has produced a documentary about them and this school, Armed With Language.

But the story of the MIS Nisei at Fort Snelling also points to a very dark and problematic part of our history. Many Nisei soldiers served even while their families were imprisoned in an internment camp, without a trial or writ of habeas corpus. And the key reason why they were imprisoned was blatant racism and the refusal of President Roosevelt, the military and the American public to distinguish between Japan the nation and Americans of Japanese descent. (In contrast, German and Italian Americans did not face such mass incarceration.)

This racist refusal to distinguish between the countries of Asia and Americans of Asian descent continues to the present, and we have unfortunately seen it increase during this past year. Clearly, America still has not learned the lesson of the injustice of the internment camps or what Asian Americans like the MIS Nisei contribute to this nation.

Martin Luther King Jr. once famously said, “We shall overcome because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” While King’s optimism was intrinsic to his fight for justice, there have also been times in America’s history when that arc has bent backwards, away from justice. And for Asian Americans during this past year of the COVID-19 pandemic, this has surely been the case.

In March 2021, in Atlanta, a white gunman murdered eight people, including six Asian-American women who worked at three separate spas; these killings galvanized the attention of a nation which has ignored the recent rise in anti-Asian hate crimes. It should be noted that Asian-American women are 2.3 times more likely to suffer such crimes than Asian-American men.

Even as an Asian American, I’m taken aback with how quickly this anti-Asian animus has spread. In the past year (2020-21), there have been nearly 4,000 reported incidents of anti-Asian hate crimes in all 50 states, a 150% increase. And there’s little sign of this trend abating. The Atlanta murders were quickly followed by other anti-Asian violence across the country.

Last year, an 84-year-old Thai man, Vicha Ratanapakdee, was violently shoved to the concrete by a masked assailant on a San Francisco street. Ratanapakdee later died as a result of his injuries. Activist Amanda Nguyen told USA Today: “It’s so absurd that I have to say ‘Stop killing us”…We are literally fearing for our lives as we walk out of our door, and your silence, your silence rings in our heads.” Manjusha Kulkarni, of the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council, has spoken of the trauma these victims feel: “So many of us have experienced it, sometimes for the first time in our lives. It makes it much harder to go to the grocery store, to take a walk, to be outside our homes.”

This association of Asian Americans with the COVID-19 virus did not occur by chance. These attacks have been spurred on by Donald Trump and the ways his rhetoric reveled in phrases like “the Wuhan virus, Wuhan is catching on,” “the China virus” and “the Kung Flu,” the latter eliciting rousing cheers at his rallies. These attacks have been spurred on by Trump’s overall encouragement of racism, xenophobia and anti-immigrant sentiment, by the ways he’s dog-whistled his followers that they should freely express their white nationalism and shun any notion of “political correctness.” And in doing all this, Trump has encouraged and exposed a long standing strain of racism against Americans of Asian descent.

Over these past months, I’ve been listening to interviews with the MIS Nisei soldiers, interviews made when they were in their seventies or eighties. These men were from my parents’ generation, the children of immigrants, and what I find hard to capture here is the tenor and timbre of the ways they talk about their experiences. The soldiers from Hawaii are a bit flashier, more outspoken, though not all; the Hawaiian Nisei come from a place where Asians are in the majority.

But for the most part, all these Nisei soldiers display a sense of humility and a certain guardedness, a quietness that reveals…but only if you’re perceptive, only if you can detect the nuances beneath their looks and words and tone.

For there are depths they don’t readily reveal, even when talking about exploits of great danger on the battlefield or troubling experiences with racial prejudice. These men - they’ve mostly passed - were deeply patriotic, but not in any chest-pounding way, not a trumpeting nationalism; theirs was not a patriotism to be worn as a badge of great distinction and fanfare or a challenge to others. In some cases, it’s almost a mumbled avowal: “I wanted to show that I'm, uh, you know, just as American as any, anybody. And this was one way to prove it,” says Bill Doi, who eventually settled in Minnesota.

One of the more well-known MIS Nisei, Roy Matsumoto, fought with the famed Merrill’s Marauders, the guerrilla fighters who worked behind Japanese lines in the deep jungles of Burma. In his interview, in a raspy voice, Matsumoto relates a series of battlefield feats of great courage, but in a manner that is quiet, matter of fact: When his unit is surrounded and can’t find a way to escape, Matsumoto crawls through the jungle to hear the Japanese commander plan an attack from a certain direction; he then crawls back and directs his unit’s machine guns towards the point of attack. The first Japanese attack is mowed down, but the second wave stops. So Matsumoto crawls back again to the enemy lines and tricks the Japanese: In his interview, he shouts the Japanese phrases he used to imitate an officer in the Imperial Army ordering the enemy’s troops to charge into the ambush. As a result, his unit survives and escapes. But then Matsumoto’s animated tone falls away into his usual, almost parsimonious and muted conversational voice; there’s no sense of bravado, no notice of his courage or even his cunning, but a sense of “I wasn’t so special, I just did what any of us would do, what any of us soldiers were doing.”

In the interviews, I’ll see something flicker across the face of a Nisei soldier, a feeling, an unspoken thought, and it’s there and not there. Their emotions, their inner life, are not, as they sometimes say in acting, highly indicated.

So when you watch this documentary, look closely at the faces of these men and consider what they contributed to the war and our country. And if you don’t know this, remember these facts: In the early 1980’s, legal researcher Peter Irons discovered that the government knew the Japanese-American community posed no military threat. But the government, the military and the Solicitor General all lied to the public about this, including in the Supreme Court.

But in 1988, prompted by Japanese-American activists, the US Congress and President Ronald Reagan apologized to the Japanese-American community and acknowledged that there was no military necessity for the internment camps. Instead, the real reasons for the camps were “racism, wartime hysteria and a failure of leadership.”

The current rise of anti-Asian American hate crimes stems from similar causes. We still have much to learn as a country, and this documentary about the MIS Nisei, Armed with Language, has much to teach us.

David Mura is a memoirist, poet, fiction writer, playwright and critic. A Sansei or third-generation Japanese American, both his parents’ families were imprisoned in the internment camps during World War II. His uncle, Tadashi Nakauchi, served as one of the MIS Nisei linguists and studied the Japanese language at Fort Snelling.

This story is made possible by the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund and the citizens of Minnesota.

PBS staffer Jada Leng offers a reflection on the March 16, 2021 mass shootings in the Atlanta area that left eight people dead, including six women of Asian descent, along with a collection of videos to watch in order to feel comfort, gain insight and raise awareness.

In the shadows of the Vietnam War, the CIA organized a clandestine operation aimed at halting the spread of communism deeper into Southeast Asia. As part of the mission, they trained Hmong soldiers, who played a critical role in intercepting the flow of supplies to Viet Cong outposts along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Discover more about the operation from the Hmong men and women who risked their lives in America’s Secret War.