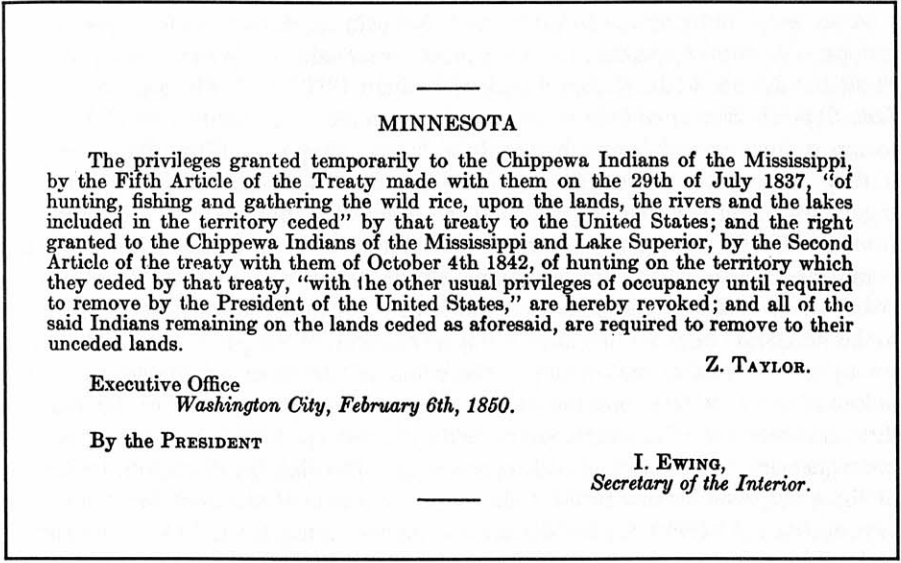

Alexander Ramsey Committed a Heinous Crime

...and many of us don't know about it.

It’s known as the Sandy Lake Tragedy, but that makes it sound like an accident. In more realistic terms, it’s about as awful a story as one could find. Carefully planned cruelty. Brazen inhumanity. Willful neglect. Corruption from the White House to our (pre-) statehouse. It’s an act of brutality so horrible that it shocked the nation and triggered a wholesale restructuring of Native American lives across the country to this day. It happened right here in Minnesota, and you probably don’t know anything about it.

It all begins in 1830, when President Andrew Jackson signs the Indian Removal Act, authorizing the US government to remove Native nations currently living on the eastern side of the Mississippi River to the western side - an act sealed with the promise of a land exchange. This law largely targets southern tribes like the Cherokee in the southeast, but tribal leaders everywhere are paying attention.

The many different Ojibwe groups of the north - whose lands spread across the entire Great Lakes and much of southern Canada - believe they are safe in remote places like northern Wisconsin. Kechewaishke (a.k.a. Chief Buffalo) is the principal chief of the numerous bands of Lake Superior Ojibwe, and a respected and recognized leader across the larger Ojibwe landscape. He has already signed four treaties (including one in 1837, which will prove important much later), but he hopes his tribe’s future is not in jeopardy. His band watches closely from their ancestral capital of La Pointe in the Apostle Islands as white settlers creep northward into Michigan and Wisconsin, prompting the removal of Anishinaabe sister tribes, the Odawa and Potawatomi. But still, the Indian agents bring their annual annuity payments and supplies to La Pointe, year after year.

Wisconsin’s achievement of statehood in 1848 suddenly thrusts the La Pointe band of Lake Superior Ojibwe into the spotlight as white business interests work to lay claim to natural resources on Ojibwe land. Kechewaishke, who has already served faithful as principal chief of this vast confederation for decades, maintains constant contact with the other bands to make sure all Ojibwe uphold their end of treaties so that the US government has no reason for call for their removal.

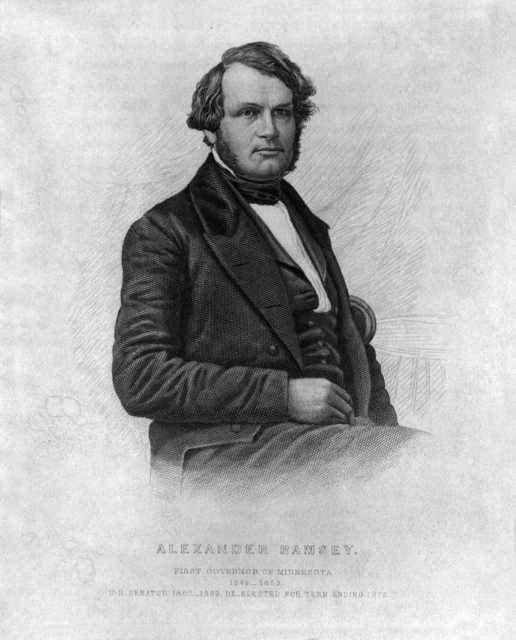

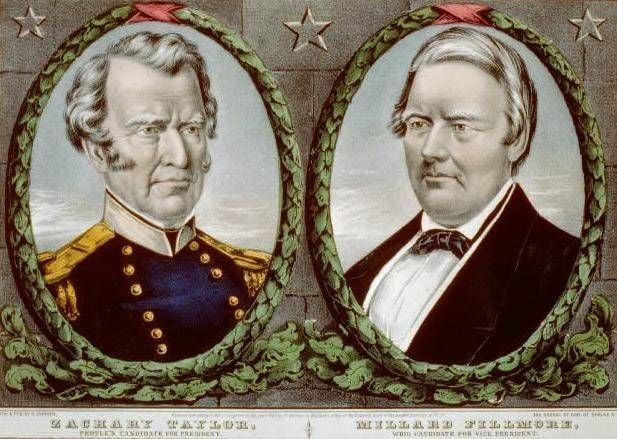

It is one of the United States’ most forgettable presidents - Zachary Taylor - who signs in February 1850 an executive order to remove the Ojibwe from Wisconsin and Michigan, and to revoke their rights to hunt, fish and gather on ceded land. The order - one of only five Taylor would ever issue - is, in fact, completely unconstitutional, breaking countless standing treaties without consent. The reaction across the Great Lakes region is quite surprising: The Wisconsin Legislature vehemently resists the order, effectively cancelling the removal as it was originally planned. Ojibwe and white residents are outraged, alike, as the Detroit Daily Free Press would later write, "The Indians are loathe to go, and the Whites to let them go." Newspapers publish editorials blasting the order, one observing, "This is a new and ingeniously contrived way of effecting the removal of the natives." Another newspaper writes, "This unlooked-for order has brought disappointment and consternation to the Indians throughout the Lake Superior Country, and will bring upon them the most disastrous consequences."

Truer words could not have been written. And here’s where Minnesota’s regrettable role begins.

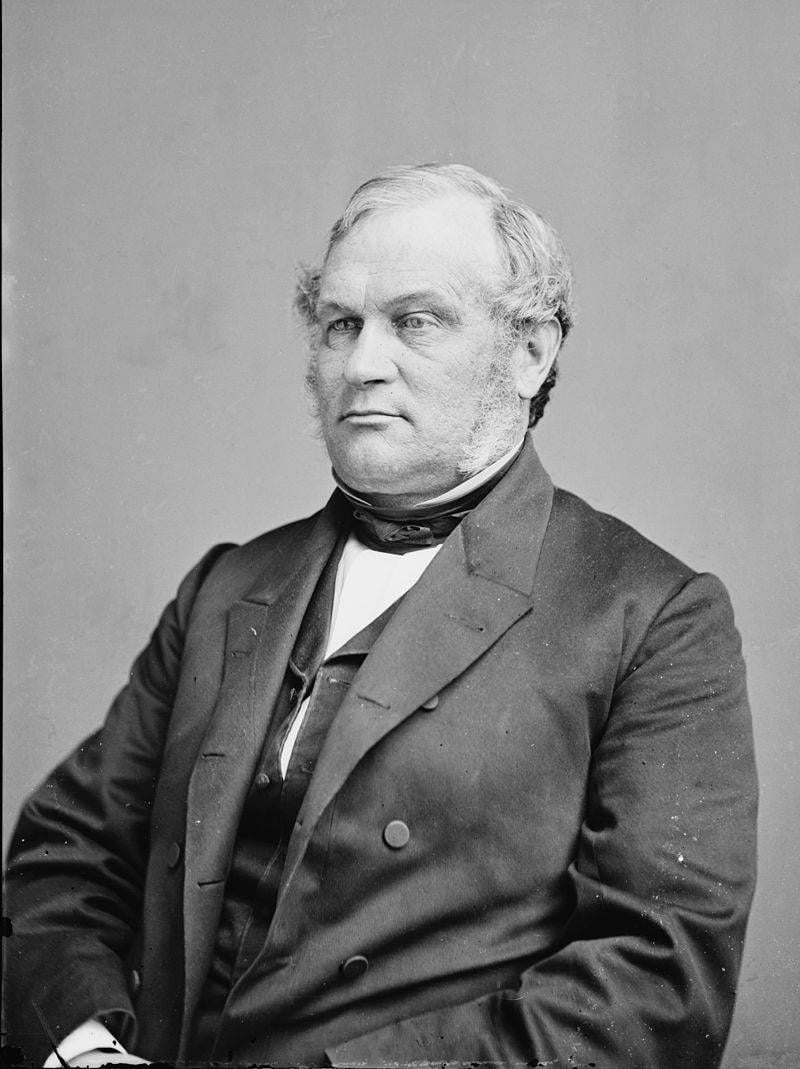

It is Minnesota’s first Territorial Governor, the much-celebrated Alexander Ramsey, who conspires with Indian sub-agent John Watrous and the Bureau of Indian Affairs to concoct a scheme to force the Lake Superior Ojibwe to relocate to Minnesota. Ramsey and Watrous will benefit financially and politically from this relocation to Minnesota Territory, and so will the Territory, as annuity payments from Washington will get spent locally. This small pack of Minnesota and Washington conspirators works in secrecy, keeping their scheme unknown by Indians and whites, alike. That June, Ramsey, Watrous and two other men head out to find potential sites for a new Indian agency in the Minnesota Territory, ultimately selecting a remote spot near Sandy Lake, about 70 miles west of Duluth. Ojibwe bands from across the area are officially notified by Ramsey that they must all move to Sandy Lake by October 25, 1850 to receive their payments and supplies. Every man, woman and child must make the journey.

On July 1, one of the chief architects of the plan - Indian Affairs Commissioner Orlando Brown - resigns. Eight days later, President Zachary Taylor dies suddenly after only 16 months in office, prompting Vice President Millard Fillmore to assume the role. On July 22, Secretary of the Interior Thomas Ewing is appointed by Fillmore to a vacant Senate seat. So before the end of July - before this illegal scheme has even begun to play out - three of its chief creators are no longer involved.

As October 25th nears, thousands of Ojibwe from the Mississippi and Lake Superior Bands converge on Sandy Lake in the Minnesota Territory, fully expecting agent John Watrous to meet them there with food, supplies and cash payments for all. Government agents provide modest food rations, which are apparently contaminated. The Ojibwe come and they wait. And wait. By November 10, some 4,000 Ojibwe are encamped at Sandy Lake. All had planned to collect their supplies and payments in late October and then return to their homelands before winter. As they wait for Watrous and his life-saving supplies, the meager, contaminated rations dwindle and spoil.

John Watrous finally arrives at Sandy Lake a month late on November 24, and is met with a scene of death, disease, and suffering. What’s more, Watrous arrives empty-handed; without congressional authorization, he can’t pay annuities, so he contracts with local traders on credit for limited provisions at outrageous prices. As he distributes provisions in early December, winter sets in. He comes back to Sandy Lake a week later on December 10 to write a report for Ramsey. Watrous records 150 Ojibwe people have died from measles, dysentery, starvation and exposure. A Mille Lacs Band leader would later testify that up to six people were dying every single day.

What's more, the conspiracy fully intended for Watrous to show up late. Indeed, it is Alexander Ramsey’s idea to delay payment, which would virtually guarantee that the Ojibwe would be unable to return home by canoe because the waterways would have frozen over, trapping them in Minnesota. But compounding Ramsey and Watrous’ planned lateness, the unexpected death of President Taylor in July had thrown Washington into disarray, and Congress could not authorize payment in time. Ramsey and Watrous have several months to call it off and warn the Ojibwe not to come, knowing they could not deliver. And yet, they choose to enact their dangerous scheme anyway.

By Christmas of 1850, newspapers report that 167 Ojibwe have died at Sandy Lake from starvation and disease. With the rivers frozen, the surviving Ojibwe must abandon their precious canoes and make their way home in the dead of winter, including the 91-year-old chief Kechewaishke. The perilous march home, on foot with inadequate supplies and weakened constitutions, claims another 230 people.

In the end, some 400 Ojibwe people are dead at the hands of Minnesota’s founding father and his partner.

A recent study suggests that 12% of the Lake Superior Ojibwe - many able-bodied men - perish in the plot. In addition to the loss of lives, countless valuable canoes and other durable goods are abandoned at Sandy Lake, months that would normally have been spent doing crucial work to prepare for winter are wasted as they wait, and future annuity moneys get promised to opportunistic traders for food and supplies intended to help the Ojibwe survive the march home, along with the rest of the winter at their unprepared camps.

As news of the disaster spreads, many white Americans are outraged at the inhumanity. Newspapers across the Lake Superior region run editorials condemning the removal effort. Ramsey, eager to dodge blame, offers this statement:

"Far from famine or starvation ensuing from any negligence on the part of Government officers, the Chippewas received all that Government was under treaty obligations to furnish to them, except their money; and this, as everyone is aware, who is at all familiar with the thriftless habits of the Indians, and the fatal facility with which they incur debts whenever opportunity presents, is usually all of it due to their traders."

Kechewaishke survives the trek, and from his home in La Pointe, implores all Wisconsinites to support the Lake Superior Ojibwe’s desire to stay in their ancestral homeland. Residents respond with calls for reservations instead. In time, Kechewaishke comes to see permanent reservations as the best way forward for his people.

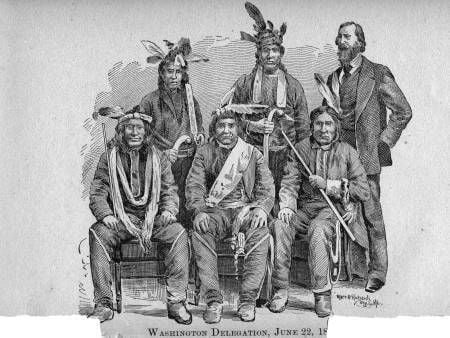

In April 1852, 92-year-old Kechewaishke and six La Pointe Ojibwe representatives journey uninvited to Washington, D.C., to protest their treatment and hopefully negotiate permanent security for their homeland. They travel first by birchbark canoe, then by steamship, gathering hundreds of signatures of support as they go. They are detained and harassed by Indian agents in Sault Ste. Marie and Detroit, who tell them to turn back, but they ultimately make their way to New York City. It is there that they garner publicity, money and public support for their cause before heading to Washington, D.C.

The party gets an icy reception from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. However, a New York congressman hears of their arrival and invites the party to join his already-scheduled meeting with President Fillmore the very next day. Fillmore - moved by the hour-long testimony of an English-speaking member of the party - promptly overturns the removal order, permanently resets the annuity payment location back to La Pointe and agrees to a treaty to create permanent reservations in Wisconsin.

Two-and-a-half years later, 95-year-old Kechewaishke signs a treaty at La Pointe, providing his people with a permanent reservation. In effect, the entire removal process and the suffering and death at Sandy Lake was for naught. Kechewaishke dies the next year, after a half century of senior leadership.

The 1854 La Pointe Treaty marks the end of US removal efforts against the Ojibwe, though not efforts to acquire their land by other means. It also marks the beginning of an accelerated rise in the creation of Indian reservations, which are seen as a way to resolve both tribal calls for separate land with sovereignty and white discomfort with in living in proximity to Native communities. The majority of communities of the Lake Superior and Mississippi Ojibwe bands across the region agree to the reservations and relocate to them, including the La Pointe group.

Without question, Ramsey and Watrous willfully break the law, but are never punished. In fact, the duo attempts variations of the same deadly annuity delay gambit again over the next two years. They even try to thwart the La Pointe delegation’s trip to Washington, D.C. Ramsey and Watrous continue their illegal and dangerous antics until 1853, when all the players get swapped out: Franklin Pierce is in the White House,George Manypenny is the Indian Affairs Commissioner, Ramsey’s territorial governorship ends, Watrous gets fired. The reservation model legitimizes land acquisition by purchase and - after an 1855 treaty with the Mississippi, Pillager and Lake Winnibigoshish bands - Manypenny snaps up virtually all of Minnesota. Three years later, Minnesota becomes a state. Ramsey’s political fortunes only blossom: next as Mayor of Saint Paul, then Governor of Minnesota (wherein he calls for the extermination of the Dakota during the U.S.-Dakota War), then U.S. Senator, and finally Secretary of War.

Ramsey also becomes the namesake of two counties, two cities, several parks and schools, even a Navy ship. Meanwhile, the devastation of his crimes at Sandy Lake is swept under the rug of history and forgotten, at least by those who can afford the luxury of forgetting.

And lest you think the story ends there, the echoes of Sandy Lake continue to ring. On the doorstep of the 21st Century, Taylor’s executive order is scrutinized by the Supreme Court, when the Mille Lacs Band sues the state of Minnesota concerning the other half of the order: the revocation of Ojibwe rights to hunt, fish and gather on ceded lands, guaranteed in that important 1837 treaty signed by Kechewaishke and 46 other Ojibwe leaders. In 1999, the United States Supreme Court finds that Taylor’s order is invalid in its entirety, and that the two parts of the order could not be separated. The nation's highest court affirms the Ojibwe rights from the 1837 treaty, an important legal victory for Native sovereignty.

That this story is not widely known, not regularly taught in schools, is rather astounding. Indeed, this author - a lifelong resident of Ramsey County - had no awareness of this story until stumbling across it a few months ago. What happened at Sandy Lake was an abomination and a crime. One hundred and seventy years later, most Minnesotans know the name of Alexander Ramsey; but if you were to utter the name Kechewaishke, most would draw a blank. And that's precisely what pulls the tragedy of this story directly into the present moment.

This story is made possible by the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund and the citizens of Minnesota.

In the early decades of the 20th Century, white Americans clamored for trinkets, mass-produced "artifacts" and musical scores appropriated from indigenous cultures. And it turns out that Minnesota also had its own "grand racist opera" that revolved around the tale of Winona, a Native American woman who, as legend has it, chose to leap from the rocky point of Maiden Rock rather than marry a suitor she did not love. Discover more about the problematic history of the "Indianist movement."

When Land O’ Lakes decided earlier this year to remove the iconic Native American maiden from its packaging, many celebrated the move. After all, members of the public had called on the company for years to remove what they considered racially stereotypical and culturally appropriated. But Mia, as she is known, was given a refresh by Red Lake Ojibwe artist Patrick DesJarlait in 1954 – and his son, the artist and activist Robert DesJarlait, has mixed feelings about the company’s decision. So we wondered: Is Mia a racist trope or a symbol of Native pride?

Discover how Minnesota-based brothers Micco and Samsoche Sampson are revitalizing another Native American tradition, the art of the hoop dance, with a dash of influence from hip hop.